It was recently reported that director Martin Scorsese will soon film A Life of Jesus, based on the novel of the same name by Japanese author Shusaku Endo. It will be the second Endo novel he has filmed, following 2016’s Silence, and his second film based on a novel about Jesus, following 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ.

I should open by admitting that I have a soft spot for the latter, written by Nikos Kazantzakis. When at fourteen I started at the Jesuit high school in town, I was a sort of spiritual but not religious Christian. When I left there for a Jesuit university, I was spiritual in a generally mainline Protestant Christian way, but still not really religious. And when I left the Jesuit university for the more or less secular divinity school, I was a devout Catholic, spiritual and religious, which I remain to this day.

A key part of this trajectory was that by the end of my first year in college, I had become a theology major, and this academic study became a vehicle (and at times a proxy) for my discernment of God’s movement in my life. I had also made a lot of friends who were driven, more than anything else, by the questions in their spiritual lives. And amid all this, I first read Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel. The presentation of a Jesus trying to figure out his vocation, one momentous for all the cosmos, struck me. Looking back at old emails, I saw I wrote to a friend about the book:

Conceptualizing the spiritual life as one of struggle and hardship has been the most sensible and impacting for me, personally. I sometimes think of the image of Jacob wrestling the angel in order to visualize how I feel my relationship with God is. And not only my relationship with God, but with myself. While I don't truck much with a gnostic worldview overall, I think it is a pretty common view of myself, in that I have both good and evil within me, and these two forces fight against each other. And more frighteningly, I don't know which side will win, in the end, whenever that comes…

But struggle works for me. It's why I liked Last Temptation of Christ so much. Even if the portrait of Jesus was flawed (as is every other portrait of him), it was a Jesus that made sense to me - one conflicted and struggling with what might have been true or might have been blasphemy. I'd give it a recommend, if you haven't read it yet.

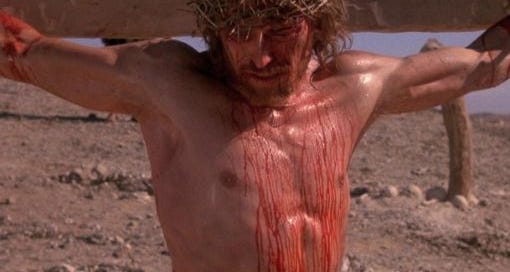

The book spoke to me. I didn’t see the film until several years later, and at the time I largely fit into the classic “I liked the book better” trope of movie reviews. Nonetheless, Scorsese’s film does maintain the conflicted, troubled portrait of Jesus that animates Kazantzakis’ novel, brought to life by the remarkable Willem Dafoe.

So here are really two things I want to do in my review of The Last Temptation of Christ: first, look at the temptations themselves that are the theme and structure of the film, and second, to look at who the Jesus of the film is. However, in order to keep things manageable, I think I need to do this in two posts. So today, temptations. Tomorrow, Jesus, with some Judas thrown in.

The film was a magnet for controversy long before its release, attracting criticism especially from Christian figures in the United States. And there is much to critique about the theological and spiritual vision of the film (more of that tomorrow). But I also must note that, by and large, a lot of the controversy around the film is most explicitly about a scene, or perhaps just the idea that there could be such a scene, of Jesus having sex with Mary Magdalene. The scene occurs around the 2:15 mark, lasts less than a minute, and is not particularly graphic. It then cuts immediately to the image of a kneeling Mary Magdalene, quite visibly pregnant. Another minute or so later, there is a bright light, Mary Magdalene smiles, and then she is dead.

This whole sequence is part of the titular “last temptation,” and it is a sequence that only makes sense if one looks back at how Scorsese depicts Jesus’ temptations in the desert. That part of the film, starting around 53 minutes in, lasts about ten minutes. It begins with Jesus tracing a large circle in the sand, telling God he will not leave until God speaks to him, and that he will accept whatever path God chooses for him.

As he sits, a snake with the voice of Mary Magdalene approaches. It says Jesus was alone the way Adam was alone, and that the serpent is not tricking him by noting his loneliness and desire for a family. It tells Jesus to save himself from this path, that he needs love. Jesus refuses to respond further, the snake explodes. The first temptation.

Next, a lion walks up to Jesus out of the darkness. This one has the voice of Judas, but claims that it is actually Jesus’ heart, which desires to conquer the world. In fact he could have any country he wants, even all of the countries. Jesus calls the lion a liar and tells it to step into his circle. The lion approaches, the lion disappears. The second temptation.

Finally, a pillar of fire bursts out of the ground, bright against the night sky. In a voice we have not yet heard in this film, it claims that as a child, Jesus would pray to be made into a god, and that it was time for him to admit his desires and join with the flame. This time, Jesus outright calls it Satan, and the fire disappears. In its place we see an apple tree, from which Jesus takes an apple. Jesus bites, the apple bleeds. The third temptation.

But then the fire briefly reappears: “We’ll see each other again.”

The three temptations themselves obviously differ from the canonical presentations in Matthew 4 and Luke 4, although the stinger is a play on the stinger of Luke 4:13, the devil “departed from him for a time.”

Yet the three temptations depicted here by Scorsese - to have a family, to be king of the world, to be a god - are interesting in how they interact throughout the film. Starting with the third temptation, Scorsese’s Jesus is deeply, obviously human, to the extent that he (like so many of us) is fearful, uncertain, sinful, running from God. It’s not the full humanity of the Council of Chalcedon, or even the “one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin” of Hebrews 4:15. He’s just another, normal human being, with the exception that he has also been selected for a mission by God (maybe), whose voice he hears (although that voice might actually be Satan’s).

Jesus’ uncertainty about the voices he hears (at times also represented by the sound of something following him, something that isn’t there when he turns around to look) connects to the temptation to be a god. Early on, Jesus struggles with his relationship to God, saying that God’s love causes him pain and that he performs ascetic practices to try to silence the voices. We learn early on that Jesus plies his carpenter’s skills to make crosses for the Romans, which they use to execute other Jews, but that he does so in hopes that God will hate him and love someone else instead.

There is a revealing early sequence in which a Jewish revolutionary named Lazarus is to be executed, and Jesus carries the cross he himself has made for Lazarus. Other Jews, including Mary Magdalene, spit or yell at him, already hating him in the way Jesus hopes that God will. After this crucifixion is over, Jesus’ mother asks him at one point if he is sure that it is God who speaks to him, and whose speech feels like torment, and Jesus tells her he doesn’t really know.

There really isn’t much evidence in the film that the desire to be God is actually a temptation for Jesus. There is even less for the second temptation, that he desires to be a king, despite what the lion suggests. There are some shouts of “king of the Jews” as he enters Jerusalem on a donkey, and Pilate asks about Jesus’ kingdom during Jesus’ trial, but even this is briefly glossed over.

Scorsese’s minimal attention to this temptation is striking in part because it is the one most strongly emphasized in other Jesus movies up to this time. DeMille’s The King of Kings only uses this temptation, placing Jesus’ encounter with Satan in the Temple rather than the desert, while Stevens’ King of Kings makes the temptation to kingship a recurring thread throughout the film, often having the Dark Hermit appear at the same time.

In fact, it is that first temptation that drives so much of The Last Temptation. Earlier, Jesus had visited Mary Magdalene, waiting in a room full of other men who were waiting for their chance to have sex with her.1 Once they are all gone and she and Jesus can talk, she is angry at him and his requests for forgiveness. But it emerges in their conversation that they have known each other since their youth, and that they had wanted to be with each other until Jesus rejected her because of God.

When Jesus returns from his temptations, he first meets Mary and Martha, who clean and feed him. Conversation soon turns to family: Martha asks him if he has a wife; when he says no, Mary asks him if he misses having a home, a family, a real life. She says “If you really want God, don’t spend your time in the desert.” God is actually found in the love of the family.

Even later, when his preaching is rejected in his hometown, one of the hearers calls him crazy, saying “See, this is what happens when a man swears off sex; the semen backs up into his brain!”

In fact, the last temptation is still the first temptation. Jesus, having cried out “Father, why have you forsaken me!?” from the cross, sees a girl who claims to be his guardian angel. She compares their situation to that of Abraham and Isaac; then, too, an angel appeared at the last minute to prevent the father from sacrificing the son. She tells Jesus that he is God’s son, but not the messiah, and so his death was not needed. In a Miltonian line, she says “sometimes we angels look down on men and envy you, really envy you.”

As they walk away from Golgotha, they encounter a procession that includes Mary Magdalene, dressed in white for a wedding (rather than the black she was wearing minutes earlier at the crucifixion). The angel confirms she is there to marry Jesus. Now they are married, then we have the sex scene described earlier, then her death. Jesus is filled with sorrow, but the angel directs him towards Mary of Bethany.

The normal, everyday family life of Jesus continues through quick time jumps. Now Jesus and Mary are married with two children, now Jesus is also married to Martha, now they also have kids. Now the large family picnics together within hearing range of Paul the Apostle, preaching the infancy narrative of Jesus, the teachings of Jesus, the resurrection of Jesus.

The angel tries to steer Jesus away from Paul, but Jesus confronts him nonetheless. Jesus tells Paul that what he’s saying is false. Paul says, on one hand, that it doesn’t matter whether it’s true because the people need it to be true, and Paul is giving them what they need. It is a cynical portrayal of both Paul and of the truth. On the other hand, though, Paul says to Jesus that he is not actually Jesus, that the Jesus of Paul is more important, more powerful, and that this weak, exclusively human Jesus is good to forget. And in his own way, Paul is absolutely right here.

At last we arrive at a much older Jesus, nearing his deathbed as Jerusalem and the Temple burn in the year 70. The angel, who has not aged a day, says it’s time for him to move on, to die, as a normal person. Yet as he lay dying, his old apostles return. Most importantly, Judas, the one who betrayed Jesus, returns and condemns Jesus for being the real betrayer. He’s the one who turned away from his mission to die on behalf of all.

As Jesus says the guardian angel saved him from all that, Judas tells him to look, to really see who that little girl is. We suddenly see again the pillar of fire, the one who tempted him to be like God, who reminds Jesus that he told him they would meet again. This realization drives the dying Jesus to crawl out of his bed, crawl out of his home, and beg God for forgiveness. Evoking the parable of the prodigal son, he prays “Father, take me back, make a feast, welcome me home. I want to be the messiah!”

At this, we return to the crucifixion, Jesus still on the cross, the women still watching in sorrow, the crowd still mocking him. Jesus smiles, even laughs, and shouts out “it is accomplished!”

The last temptation sequence lasts about 30 minutes, roughly 20% of the film’s running time. The scenes that most people are most upset about occur here. But these scenes are a temptation, portrayed as a vision, that Jesus rejects. Twice Satan tries to pull Jesus away from the cross by focusing on family, on love, on a normal, everyday life, and twice Jesus rejects him.

I don’t dispute that the scenes from this vision are jarring, even disturbing. They’re probably not for everyone. But I think part of why I am fascinated, both spiritually and theologically, by the temptations of Jesus in Matthew 4 and Luke 4 is that they are also disturbing. To be tempted cannot itself be sinful if Jesus is tempted, but temptations can be a path to sin, one which I suspect all of us struggle with. There is a tiny, fine line somewhere between what Jesus experiences and what we would understand to be sin, and that line disturbs.

Although the temptation to have a family and live a normal life is not one of the three canonical temptations of Jesus, I don’t in principle find it jarring to imagine that Jesus could have been tempted by that. To be outraged by the film (or the book) because of this sequence seems overwrought, to be honest.

If one is to be upset about the film, I think that is better grounded in the wider portrayal of Jesus himself, not in the temptations. I’ll return to this aspect tomorrow.

This scene, and the consummation of their marriage in the final vision, are the two sex scenes of the film. Nonetheless, Tim Penland, who had been hired by Universal to help work with Christian leaders before the film was released but later resigned, described it as “a sex film about Jesus Christ” on James Dobson’s Focus on the Family (Thomas R. Lindlof, Hollywood Under Siege: Martin Scorsese, the Religious Right, and the Culture Wars (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2008), 166).