Our Hearts Burning with the Glory of God

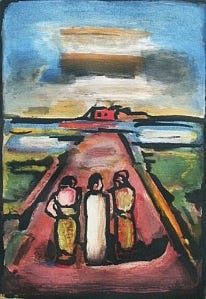

The story of the Road to Emmaus begins in Luke 24:13. It tells us of Cleopas and his unnamed companion, who unknowingly encounter the risen Christ as they walk away from Jerusalem.

Importantly, however, the story follows the women (Mary Magdalene, Joanna, and Mary the mother of James) reporting the empty tomb to the disciples. While Peter took off to see for himself, the rest thought the report of the women was “nonsense” and “did not believe them” (Lk 24:11).1 Cleopas and his companion are among these unbelievers, and they take off for Emmaus (7 miles away, or about two hours on average).

When Jesus the stranger sidles up alongside them, they recount what has happened, even up to that morning:

Some women from our group, however, have astounded us: they were at the tomb early in the morning

and did not find his body; they came back and reported that they had indeed seen a vision of angels who announced that he was alive.

Then some of those with us went to the tomb and found things just as the women had described, but him they did not see. (Lk 24:22-24)

While “their eyes were prevented from recognizing” Jesus, they nonetheless listened to him as he “interpreted to them what referred to him in all the scriptures” (Lk 24:17). They are so drawn in by his narrative, and his companionship, that they ask him to stay with them. They show hospitality to this stranger, sharing a meal and a place to stay. Even though they seem unsure about what to believe amidst tragedy, their practices remain soundly what their master taught.

The climax of the Emmaus story occurs during that meal:

And it happened that, while he was with them at table, he took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them.

With that their eyes were opened and they recognized him, but he vanished from their sight.

Then they said to each other, “Were not our hearts burning [within us] while he spoke to us on the way and opened the scriptures to us?” (Lk 24:30-32)

We interpret this, rightly, as Eucharistic – they finally come to recognize Jesus in the breaking of the bread. It matches with the last supper in Luke 22:19, but instead of continuing with “This is my body,” Jesus disappears from their sight.

However, although we are right to take this as the narrative’s climax, we are wrong to take it as its end. Indeed, the next part is arguably as striking:

So they set out at once and returned to Jerusalem where they found gathered together the eleven and those with them

who were saying, “The Lord has truly been raised and has appeared to Simon!”

Then the two recounted what had taken place on the way and how he was made known to them in the breaking of the bread. (Lk 24:33-35)

At once. Recall that their invitation to Jesus the stranger included saying “the day is almost over.” They don’t spend the night in Emmaus; they return immediately and walk the two hours back to the other disciples. They recount their experience, one that confirms and expands on what the women had told them earlier that day.

Is this a story about vocation? Cleopas and the unnamed companion were among the disciples, and disciples are called. But they also walked away, towards some other town, disbelieving of the report of the resurrection they’d received. Upon recognizing Christ in the breaking of the bread, they recognize their “hearts burning within” them, and immediately walk back towards the other disciples, their community. So what can this tell us about vocation?

”Were not our hearts burning within us?”

Cleopas and his companion see that their hearts were burning within them as the unrecognized Jesus unfolded the scriptures for them. Although they only see this in hindsight, it shows that their vocation is revealed in the stirrings of the heart. Ignatian spirituality teaches us that each of us finds our vocation in the deepest desires of our heart, the desires that are truly joyous and oriented to God. Indeed, God gives this vocation to each person, who lives out that vocation in their own specific situation, history, and life.

“…all the faithful of Christ…are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity”

This passage from Lumen Gentium 40 reminds us of the universal vocation to holiness. Everyone, independent of “rank or status,” is called to be holy. And again, we live that call in our own particular situation. Often when we talk about vocation, that idea gets limited to religious life, or religious life or married life, or something along these lines. But our calls are more specific even than that. As I follow this call to holiness, I know that call is bound up with my marriage to my wife, with my career as a theologian, with my friendships, and even with the particular struggles I face in my spiritual life. In each of these aspects, and in many more, that call from God to be holy pings on my soul, beckoning me to an ongoing conversion of heart.

”The glory of God is the human fully alive”

In this famous (if debatable)2 translation of St. Irenaeus of Lyons’ “Gloria Dei est vivens homo,” the message seems to be that the “fully alive” human isn’t about wish fulfillment or adrenaline-seeking; it’s about being the persons that God made us to be. I am most fully alive when I am oriented to God, when I am turned towards the divine, when I am open to the working of grace in my life. This fully alive human in fact follows the deepest desires of their heart, where that particular call to holiness is found.

Indeed, turning back to the Road to Emmaus, the connection becomes clearer when we think about names. Although the companion is unnamed, scholars tell us that Cleopas is the shortened form of Cleopatros. The Greek roots of this name translate for us as “glory of the Father.” His name describes the human being fully alive. And he recognizes this truth in the breaking of the bread and the burning of his heart.

Cleopas answers his vocation to holiness amidst his sorrow over the death of his leader, amidst his doubts about the resurrection, and amidst his friendship with the unnamed companion. He reckons with it partly on the road to Emmaus, but even more powerfully on the road back from Emmaus.

We too are called to follow the burning of our hearts, to see how God beckons us where we are, and to continually turn back to the holiness that is our calling.

Although originally written in Greek, it comes to us from Latin as “Gloria Dei est vivens homo.” Some resist this English translation because it sounds like the “cult of self-fulfillment” or some kind of new age-y mantra. However, the Catechism of the Catholic Church nonetheless has the English translation “the glory of God is man fully alive” (CCC 294), and the “self-fulfillment” interpretation is not a necessary reading of that translation (as I hope I’ve shown above).