In working on this series on movies about Jesus, I thought it would be good to go to the beginning. This turns out to be impossible, though, as some of the earliest films about Jesus are lost to history. There were five such films released between 1897 and 1898; of those, only La Passion (1898) by the Lumière brothers remains.

This version on YouTube has an added score from Bach; you can also view the film without music on the Library of Congress' website.

To understand this movie as an interpreter of the gospels, it’s necessary to emphasize how early its 1898 production was. Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope was introduced in 1893, and the Lumière brothers invented their Cinématographe in 1895. The early technical limitations of the devices, coupled with the newness of the medium, shaped the early approach to filming.

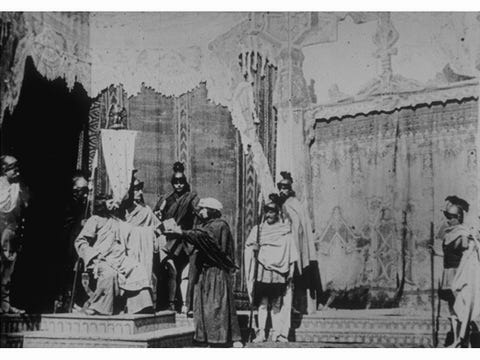

Thus many early films were a minute or shorter; this one is composed of thirteen vignettes from the life of Christ that are all in that range.1 Each one was shot by a stationary camera with a fairly wide angle on the action, fairly similar to what one would experience watching a stage performance. The resulting distance from the actors encouraged a highly demonstrative form of acting that was typical of early films.

Watching La Passion, and thinking about the scriptural, theological, and cinematic questions I used to ask my students, there were three main things that struck me:

First, given the constraints of the medium, it’s interesting how it attempts to compress or adjust certain aspects of the narrative of the life of Jesus in the apparent name of efficiency. For example, in the “Adoration of the Magi” vignette that opens the film, both the shepherds and the three wise men are brought in at once in the same way that many do with their nativity sets. The lone shepherd does appear first, although he looks like he is mostly there to show the three wise men into the stable. Perhaps the original adoration of the shepherds has already narratively taken place, off screen, but here the adorers from the Gospels of Luke and of Matthew are harmonized in one.

Similarly, the third scene is the “Raising of Lazarus.”2 Rather than having a camera follow Jesus as he comes to Lazarus’ tomb (which would have been more challenging technically), Lazarus’s corpse is brought forward on a stretcher, covered in a burial cloth. Pointing at the corpse, and then to the sky, Jesus brings Lazarus back to life. Lazarus pops up with an almost confused look on his face as the mourners fall to their knees. In a twist of the narrative from John 11, the Lumière brothers set the scene up so that the chief mourner is Lazarus’ wife rather than his sister (“Sa femme éplorée a supplié le Christ de lui rendre son époux”). The decision to do so has confused some viewers, who alternately suggested that the vignette looks like Jesus’ raising of the son of the widow of Nain in Luke 7.

Another odd adjustment comes from when certain followers of Jesus are present. In particular, Joseph his father, Mary his mother, and Mary Magdalene are the most consistent presence in his life. The first two are understandably present at both the “Adoration of the Magi” and the “Flight into Egypt” scenes, the two that are tied to infancy narratives in the Gospels. But the trio is also present from Jesus’ arrest all the way through his resurrection. While the Gospels attest to the two women being present for the crucifixion, the inclusion of Joseph throughout is an odd divergence from the Gospels that only feature him in the nativity stories.

The only other distinct disciple is Judas, who appears in the scenes you would expect; remaining followers are generic and interchangeable during Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem and the Last Supper. Later films will highlight the apostles, especially as stand-ins to mediate Jesus to the audience, so the choice to downplay them while maintaining the trio of Joseph and the two Marys is interesting.

These kinds of changes and compressions are a feature of nearly all depictions of Christ, and they continue because of the constraints that continue in the medium. Even as later film and television have more complex and interesting cinematography, more realistic acting, and (of course) dialogue, there are still limits on time and attention, on the ability to enter into the minds of the characters, and even on what to include, to ignore, and to add to the source material. Few films simply adopt the dialogue directly from the Gospels, but rather add and embellish. Almost all try to fill in gaps in the narrative.

Second, the film does what it can to show the otherworldly, miraculous sense of Christ. In addition to the miraculous raising of Lazarus, the film also shows Jesus suddenly and miraculously appearing to the disciples at the “Lord’s Supper.” The film does this with a jump cut, a then new technique attributed to fellow pioneer Georges Méliès. As filmed, it seems almost like an inversion of the Emmaus story in Luke, in which Jesus suddenly disappears after the breaking of the bread; one wonders if that image might have been in Lumière and Hatot’s mind.

Similarly, in the closing “Resurrection” vignette, amid sleeping Roman soldiers, Jesus pushes off the top of his tomb and begins to rise (the version I’ve seen does not get far into this rising, so I’m not sure how long the original was). The image of the tomb is not a cave with rock rolled in front of it, but rather a sarcophagus like that in Piero della Francesca’s The Resurrection.

The techniques for presenting Jesus as otherworldly are pretty simple, with the jump cut being the one clear example of what would come to be part of the cinematic grammar. Moreover, the framing of the various shots in the versions of the film available, even as relatively wide shots, has the strange effect of making any character who kneels, as in worship, effectively disappear from the screen. Yet even within this new and limited grammar, an effort is made to show Jesus as something other than just another human, as someone whose connection to God is powerful and unique.

The third feature that struck me in the film was the sets. The sets used in the film are quite simple and, well, obvious. You can see clearly the shadow of the cross against its backdrop, maybe a couple feet away, in the 11th vignette, “Calvary.” Descriptions of the film note that across the 13 vignettes, there are only 8 sets in total, but even this somewhat exaggerates. The Crucifixion/Calvary set and Entombment/Resurrection sets are the same backdrops, only shifted slightly. The same tree appears in five different scenes across three “sets.” This indicates clearly the film’s indebtedness to the stagecraft of live performance.

Symbolically, though, the recurring use of trees recalls for the viewer the importance of tree imagery and its connection to crucifixion. The specific tree used so repeatedly in the film first shows up at the Resurrection of Lazarus. This story in the Gospel of John serves as a sort of pivot towards Jesus’ crucifixion: it is subsequent to this sign that “from that day on they planned to kill him” (John 11:53). With the exception of his flagellation before Herod in the 8th vignette, every scene from Jesus’ arrest onward prominently features a large tree. It might be giving the Lumière and Hatot too much credit, but the imagery does evoke Paul’s “Christ ransomed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us, for it is written, “Cursed be everyone who hangs on a tree” (Gal 3:313).

La Passion is, overall, probably most interesting as a historical object of curiosity. I have a lot of trouble imagining showing it to my students or of their getting much out of it as a theological exercise. The quality of the available recordings is not great, and it’s often difficult to tell characters apart. Moreover, the distance of the actors from the camera, the demonstrative acting style, the staccato series of scenes each make it difficult to assess much about the inner life of Jesus in the film.

Yet it is, ultimately, an effort at interpretation. In this regard, what is most striking is that Lumière and Hatot are interpreting the Gospels into a brand new idiom, one whose grammar was in its infancy, only just stepping out from the theatrical passion plays that gave rise to it. With basically no precedent, they had to select the stories to tell, leaning heavily towards the passion and resurrection rather than teachings or most of the miracles, and devise the best way to portray them.

La Passion is the last remaining example of how cinematic pioneers sought to interpret the gospels. I don’t really think it stands on its own, per se, but its importance for the films I’ll write about in the coming weeks should not be overlooked.

Next week in the Celluloid Christ series: From the Manger to the Cross (1912), directed by Sidney Olcott. You can find links to all the posts as they come out in the series page.

Descriptions of all thirteen vignettes from the Lumière catalog, translated into English, can be found at this link.

The versions of the film available on YouTube and at the Library of Congress are missing the original third vignette, “Arrival in Jerusalem,” and instead place the “Resurrection of Lazarus” in third position.