Dear reader, let me first apologize for the long break between my last entry, on The Greatest Story Ever Told, and on today’s post about Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth. My delay in writing stems in part from the usual end of semester obligations, but even moreso from my failure to realize that Jesus of Nazareth would be six and half hours long. Providentially, this pushed my opportunity to watch it well into Advent, a season of waiting.

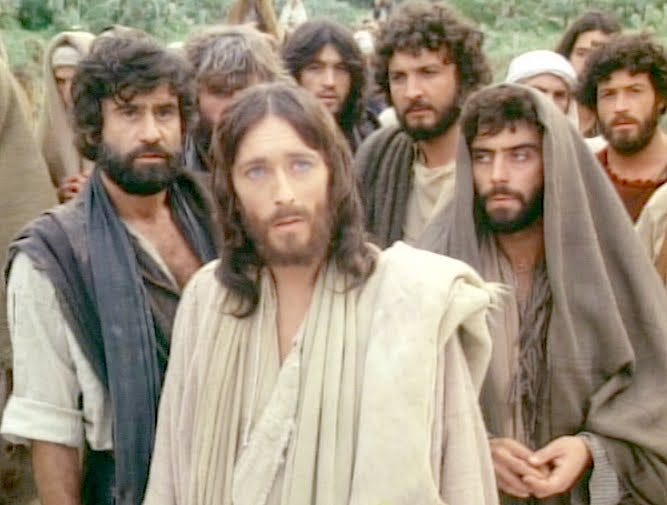

Not knowing that Jesus of Nazareth was a miniseries in four parts rather than a normal, 2-3 hour film, it was on the top of my list when I had the idea for this series on Jesus in film. I had obviously never seen it before, but I could clearly picture the DVD cover with Robert Powell’s Jesus, bearing the crown of thorns, imploring heaven with his piercing blue eyes.

That image, and others from his portrayal of Jesus, are so ubiquitous that even forty years later, Powell still tells stories about images of his Jesus showing up in Churches all around the world. When I showed a clip of the miniseries to my wife, she even asked “why is this my image of Jesus?”

One of the benefits of Jesus of Nazareth’s extended run time is that it can let the story breathe much more than the other films in this series. It is not totally comprehensive of the Gospels - among others, it has no depiction of the temptations or the transfiguration - but it does a surprisingly good job of incorporating and weaving together so many pieces from the four Gospels. As a result, it offers an interesting approach to answering the great Christological question “who do you say I am?”

This famous question comes up in one of the two scenes I want to highlight in the film. Jesus gives instructions to his twelve disciples before sending them off, two by two, to preach the gospel. Although we don’t see any of their missionary efforts, we hear about them a couple scenes later. Standing around a fire, the reunited disciples are swapping stories about miracles they performed and about the feeling God preach through them. They exhibit the sort of excitement people often have when returning from a spiritual retreat.

This prompts Jesus to ask “who do the people in Galilee say that I am?” Their conviviality from story time continues. But when he asks them “and who do you say that I am,” the mood shifts. They become pensive, uncertain; eyes are cast down. The camera pans through the circle of disciples before landing on Peter, who says “I say you are the Messiah, the Son of the Living God.”

Much as it is in the Gospel of Mark, the scene is a pivot in the miniseries. Jesus affirms what Peter says about him, and says that when the time is right, they will head to Jerusalem. Judas is especially excited (more on this below), but Jesus reveals that he will be rejected, mocked, killed, and ultimately resurrected. His disciples finally learn the stakes of what they are doing, stakes most of them will resist or run from when the time comes.

Moreover, the question of “who Jesus is” grows more and more urgent from this point forward. Each of the major camps asks it in its own way, and with their own stakes. The zealots have been plotting to kill Herod and overthrow Rome, so they want to know if Jesus will lead them in this. Caiaphas also fears the might of Rome, as well as challenges to his faith, so he wants to know if Jesus is a false prophet. Pilate wants to know why the Sanhedrin is so concerned about an itinerant carpenter with a merry band that they summoned him back to Jerusalem, but also whether he sees himself as a king and thus a possible challenge to Rome.

And of course the disciples know who Jesus is - the Messiah, the Son of the Living God - but they do not understand what that means, nor do they initially have the fortitude to endure what that entails.

However, it is also worth noting the progress the disciples do make in the film. My other central scene, which is from earlier in the miniseries, I think zeroes in more clearly on Zeffirelli’s answer to “who do you say I am.” This scene is built around the parable of the Prodigal Son.

In the Gospel of Luke, the Prodigal Son is sort of prefaced by the parables of the lost sheep and the lost coin. As Amy-Jill Levine writes in Short Stories by Jesus, the three parables share a structure that sets up expectations in the first two, only to subvert them in the third.

There is a lost sheep, a shepherd who searches and finds, and then rejoicing and a party.

There is a lost coin, a woman who searches and finds, and then rejoicing and a party.

There is a lost son, a father who does not search for him, a perhaps unexpected return, and then rejoicing and a party. And then there is an elder, resentful son who refuses to join in the rejoicing and the party, a father who goes out to him, and an exhortation to celebrate the return of the “dead” brother.

The parable ends, as Levine writes, “with two men in the field, one urging and comforting, the other resisting, vacillating, or reconciled—we do not know.”1

In Jesus of Nazareth, the setup for the parable is very different. Andrew has invited Jesus to come to Capernaum and meet Andrew’s brother, Peter. Peter is much more concerned about the weak catches he has pulled recently from the Sea of Galilee and with the predations of Matthew, the local tax collector. Peter, quite frankly, has no time for Jesus or any other prophets. Jesus persuades Peter to head back out into the water. Yet despite the immense haul of fish, and the great interest this generates in town, Peter remains resistant to Jesus. He just wants to be a simple fisherman.

Yet Jesus comes to his house, and people climb over the walls just to hear Jesus teach. Having heard about the great catch, Matthew comes, partly to collect some back taxes from Peter, and partly to hear Jesus. He is roundly booed on arrival by the assembled crowd, and honestly looks like he is enjoying how much everyone hates him. Peter tries to throw him out, but Jesus says “You seem to be most unwelcome here. I don’t know your name, but I know what you do.” Jesus then invites himself over to Matthew’s house for dinner that night. Peter and the other disciples are aghast and try hard the rest of the day to persuade him not to go. When time for dinner comes, Jesus goes to the house, but his followers all stand outside at the door. Peter, initially sulking by his boat, eventually comes to listen at the door.

It is once he sees Peter at the door that Jesus begins to tell the story of “a certain man had two sons.” Jesus tells the full story from Luke 15, letting Jesus narrate it for five full minutes of screen time. While telling the story of the younger son, he often looks at Matthew, and the camera shows us Matthew’s face changing as the story sinks in. Yet as he shifts to the elder son, he looks more and more directly at Peter, standing in the door. At the end of the parable, Jesus stares straight at Peter (and into the camera), saying “Your brother was dead,” and then immediately turns to Matthew to say “and now he’s alive again.”

Peter immediately enters the room, asks Jesus’ forgiveness for being “just a stupid man,” and then walks to Matthew. He places his hand on Jesus’ shoulder, just as Jesus had done moments before when Peter asked his forgiveness. They reconcile, and subsequently throughout the miniseries are shown together as friends, even brothers.

The five minute sequence of Jesus telling the parable is incredible, and was one of the most riveting sequences I’ve seen in any of the films in the series so far. Taken together with its preface, it reveals a couple key aspects of the Jesus in Jesus of Nazareth.

One, Jesus is not actually omniscient, as his first exchange with Matthew shows. There are other examples throughout the production where Jesus either doesn’t know who people are or about recent events, such as John the Baptist’s arrest. This fits with Zeffirelli’s stated goal to depict Jesus as “an ordinary man - gentle, fragile, simple.”

Two, Jesus has a tremendous spiritual wisdom. He has only briefly met both Peter and Matthew, but he quickly sized them both up. He recognizes this encounter as a potentially pivotal moment, with both Matthew and Peter surrounded by their respective social circles, and he cuts to the quick of their respective problems.

Third, Jesus is profoundly charismatic. It’s obvious that his miracle working gets him in the door, often literally. Whether it’s the great catch of fish here or the raising of Jairus’ daughter, tale of his works spread and people seek him out. But when he speaks, people are rapt. Throughout this story (or in his encounter with the rich young man), except for his voice you could hear a pin drop. People shift from talking, laughing, joking, working, moving around, and simply stand transfixed by his words. In many cases, people are visibly reflecting on what those words mean for their lives.

In constructing the portrayal of Jesus for the film, one of Zeffirelli’s instructions to Powell (as well as to Lorenzo Monet, who played 12 year old Jesus) was not to blink.2 We see Jesus’ face constantly throughout, often in close up, and his eyes blaze as he locks in on other characters (in my notes, I wrote “staring contest” during the sequences with John the Baptist, Peter, and the Pharisees when Mary Magdalene kisses his feet and anoints him). The blinkless approach, as well as the makeup effects to emphasize Jesus’ bright blue eyes, supports the charismatic and otherworldly presence of this Jesus.

Part of what is so interesting to me about Zeffirelli’s portrayal of Jesus is that it’s somewhat difficult to pin down questions about the humanity and divinity of this Jesus. On one hand, he is the “ordinary man” Zeffirelli wanted (and that so enraged Bob Jones III and other fundamentalist Christians, although apparently without their actually seeing the film). He has sort of normal, human limitations to his knowledge. He is at times funny, usually with a dry wit. During the Agony in the Garden, he is quite stricken while asking for the cup to pass from him. He is clearly burdened and in pain during his scourging, cross carrying, and the crucifixion.

On the other, Powell’s Jesus has distinct, set apart, otherworldly demeanor that no other character in the film can match. He performs miracles, raising two characters from the dead, healing the paralytic, giving sight to the blind, etc. There is an incredible intensity to his voice during the Last Supper as he says “this is my body.” He identifies his connection to God the Father even more explicitly than Jesus in the Gospels: when Caiaphas asks him, point blank, “Are you the Messiah, the Son of God,” the camera slowly zooms in on Jesus’ face and he says “I am.”

I think better than the other films I’ve seen so far, Zeffirelli makes a good effort both at depicting the two natures of Jesus and with trying to hold them united in one character, despite the difficulties this presents for the actors and for the medium of film. Perhaps the blinkless approach becomes a sort of metaphor for this, a mostly unwavering stare at the mystery beyond human comprehension of the eternal Creator of the universe being born, living, and dying in time.

The other major character that I feel compelled to comment on is, unsurprisingly, Judas. This is probably partly because he’s portrayed by Ian McShane, who will always be Deadwood’s Al Swearengen to me, and whose voice is unmistakable.

But it’s also because Jesus of Nazareth, like a lot of other Jesus movies, sort of doesn’t know what to do with Judas. Judas shows up fairly late in Part II of the miniseries, attending the burial of John the Baptist with a group of zealots. He has heard Jesus preach and is impressed. He begs the zealots to let Jesus continue his mission without interference and says he believes he might be the Messiah. He sets off, saying that he hopes Jesus will accept him as a disciple. Yet throughout Parts III and IV of the miniseries, Judas often seems marginal as a disciple.

When they first meet, he offers himself to Jesus, noting that he is a scholar who knows multiple languages (and thus is essentially a scribe). He is sent off like the other eleven, two by two, to spread the gospel. When the disciples are all back together, Judas has a plan for Jesus going to Jerusalem, being backed up by zealots, and meeting with the Sanhedrin, but Jesus shoots the plan down (remember, he is going there to die).

When we come to the entry in Jerusalem, Judas has gone ahead to make arrangements with a scribe named Zerah (invented for the film and played by Ian Holm, aka Bilbo Baggins from the Lord of the Rings movies). Judas’ plan is for Jesus to speak before the Sanhedrin, win them over, and thus unite the Jewish people. So Judas watches the triumphant entry from a distance, and shows up late to the commotion after Jesus cries “woe to you Pharisees.” Later, most tellingly, Judas is not at the Last Supper at all. He’s not late, he’s not sent away, he is simply absent.

With this marginalization, we also never see Judas arrange a betrayal of Jesus. Instead, he simply shows up at the garden with Zerah and temple guards and gives Jesus the kiss. When Jesus calls him a betrayer, he shakes his head; when the other disciples call him a traitor, he denies it and says the Master must speak to the Sanhedrin.

This was Judas’ big plan, with hopes that members who supported Jesus (Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea) would be able to sway Caiaphas and the others to hear Jesus out. Judas thought he had an understanding with Zerah the scribe to this effect, but after the arrest Zerah turns him away, saying there will be a trial, not a meeting. Zerah then, quite dismissively, gives him a bag of coins, and Judas is crushed.

Thus in Jesus of Nazareth, Judas is maybe an idiot, but not really the traitor. Yes, he fails to understand completely Jesus’ mission, although not evidently more than the other disciples (a point Peter passionately makes to the remaining disciples while they hide from the authorities). If anything, he ends up the one betrayed, by Zerah, who manipulates Judas into handing over Jesus under false pretenses. While the other movies I’ve watched have tried to give Judas a meaningful motivation for betraying Jesus, Jesus of Nazareth instead reframes Judas’ actions so that he is tragic and misunderstood, an idealistic sucker.

It’s an interesting move, and it definitely differentiates this Judas from the others. But I also found it kind of annoying that the miniseries felt the need to invent a new character to be the vehicle of treachery rather than the Gospel character who already fulfills that role.3

In the end, Zeffirelli made a quite beautiful and often riveting portrayal of the Gospels. It’s very very long, it’s a bit uneven, and it might be difficult for repeat viewings. But like its protagonist, it is both unblinking and reverent in depicting the Gospels.

Stray thoughts about Jesus of Nazareth:

Let’s start by noting that this miniseries exists because of Pope Saint Paul VI, who encouraged producer Lew Grade to make a miniseries about Jesus following his 1974 movie about Moses. The Pope later praised the miniseries publicly on Palm Sunday, just before it premiered on Italian TV.

It’s interesting to compare this movie to The Greatest Story Ever Told, a movie I criticized for what is effectively stunt casting for a lot of roles. Jesus of Nazareth is also chock full of famous people from the era, including Christopher Plummer as Herod, Anthony Quinn as Caiaphas, Ernest Borgnine as the centurion, Laurence Olivier as Nicodemus, etc. However, the casting feels much less gratuitous because the characters are largely given motivations that make and their roles are integrated effectively into the overall story.

Among the cast, Donald Pleasence plays Melchior, one of the three wise men. In The Greatest Story Ever Told, he played the Dark Hermit/Satan character.

There’s a really odd scene towards the end of Part III when Jesus heals the blind man. The blind man is actually resists being healed, does not want his sight, and is dragged before Jesus by a crowd. Even as Jesus puts the mud over his eyes, the man pleads to be left alone. He is quite grateful afterward, praising Jesus for the gift of his sight. In a contemporary context with so much discourse around consent, it is a jarring scene. It also contrasts with so many other scenes of characters seeking Jesus out for aid, which often end with Jesus saying “your faith has healed you.” The same is not said to the blind man.

Next time in the Celluloid Christ series: The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. You can find links to all the posts as they come out in the series page.

This is my last post for 2023. Thanks to all of you for reading, and especially to the paid subscribers, for your support this year. In January I’ll write about some goals I have for the year, and also ask what readers might be looking for.

Amy-Jill Levine, Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi (New York: HarperOne, 2014), 46.

In some writing on the film, people say Powell never blinks, or he only blinks one time - when he plays Jesus’ corpse right after the crucifixion - but you can see him blinking repeatedly in the Prodigal Son scene. Otherwise, yes, as best I could tell he does not blink.

I might have to revisit this part later when I review The Last Temptation of Christ, which also has an unusual reading of Judas.