David Tracy, a Roman Catholic priest and theologian who taught for decades at the University of Chicago, passed away last night. He had been in and out of hospital in recent weeks, but he slept peacefully during his final days and was not in pain. His nieces and nephews were with him in Chicago at the end.

David Tracy was born in Yonkers, NY, in 1939. He first felt a calling to the priesthood at age 13, not long after the death of his father. Following seminary studies in New York, he spent most of the 1960’s in Rome at the Gregorian University, first receiving his Licentiate in Sacred Theology (STL) in 1964 and returning to study for the Doctor of Sacred Theology (STD) under Bernard Lonergan, SJ in 1965. He spent the intervening year at Saint Mary of Stamford parish in the Diocese of Bridgeport, where perhaps most notably he persuaded conservative commentator William F. Buckley to serve as a lay lector at mass.

His first teaching position, at the Catholic University of America from 1967-69, brought him to public attention as one of the 22 CUA faculty who were fired for their public dissent from Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae. Although he and the others were ultimately given back their jobs, he took an offer from Dean Jerald Brauer to join the University of Chicago Divinity School, where he remained until his retirement in 2006.

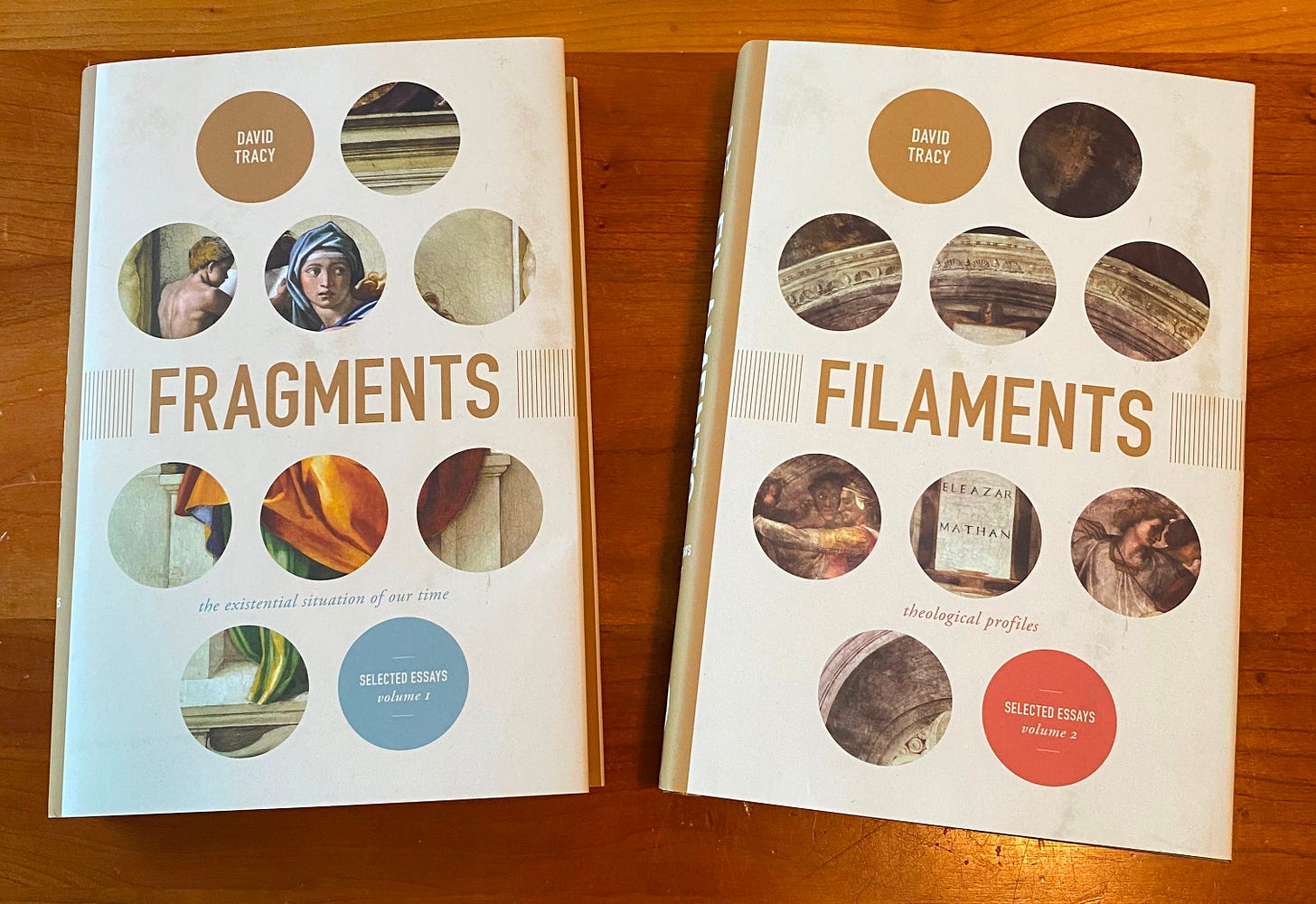

He wrote extensively, authoring nine books and co-editing several more. The most influential of these, The Analogical Imagination,1 set out Tracy’s key positions on public theology, theological method, and the religious classic. In 1986, he was the subject of a cover story for the New York Times Magazine, “A Dissenting Voice: Catholic Theologian David Tracy,” by Eugene Kennedy.

Probably the highest theological honor he received was the invitation to give the Gifford Lectures at Edinburgh for 2000. He had intended to publish them under the title This Side of God around 2003, but this didn’t happen. Although Tracy continued to work on the lectures, expanding, adjusting, revising, for subsequent decades, they were never published. It’s possible that their current iterations will be edited and published posthumously, but I have no special insight on that.

As much as that brief biography is accurate, I think it falls short of expressing Tracy’s personality and generosity. To supplement, I’d like to offer a couple brief stories of my own.

The first time I met David Tracy, I was maybe a few weeks into my masters degree at the University of Chicago Divinity School. I shared an apartment on Cornell Ave in Hyde Park with my friends Andy Staron and Heath Carter. Andy, who was taking a course with Tracy, called me to ask if I would be able to give him and Prof. Tracy a ride home, as Tracy lived a block or two from our apartment. We had read Tracy in the theology program at Georgetown and I was well aware of his intelligence and stature in the field. As I so often was with some of the Divinity School faculty, I was both nervous and excited to talk with him.

Now, to give some context to the story, I should note that I had bought my car, a used Oldsmobile Alero, the summer before I started divinity school. Moreover, at the Easter Vigil earlier that year, I entered the Catholic Church. So new Catholic, new car, and I would now be giving a priest-theologian a ride home. Seemed like a good opportunity to have the car blessed.

I pulled up in the circle close to Swift Hall, and introduced myself to Tracy as he got in the front seat and Andy got in the back. I proceeded, with all the earnestness one could muster at 22, to ask him to bless the car. He said ok, held up his hands, fingers outstretched, and said “BZZZZZT,” simultaneously blessing the car and giving his best impression of Emperor Palpatine trying to kill Luke Skywalker.2

I did not, at that moment, know that I would write my dissertation on David Tracy’s theological anthropology.

About seven years later, I was well into my PhD program at Boston College and trying to nail down my dissertation topic. My first pitch to my original advisor, Roberto Goizueto, was a quite ambitious project on technology and theological anthropology, focusing on how the “information society” shaped and was shaped by particular theological anthropologies. It incorporated potentially several different major figures on anthropology (Balthasar, Lonergan, Schillebeeckx), with Tracy being a somewhat late addition to that.

Goizueta helped me work through my ideas and encouraged me to narrow my scope, while Mary Ann Hinsdale (who became my director) helped me further realize that focusing on Tracy’s anthropology alone would give me something that (a) hadn’t really been done previously and (b) would be manageable as a project.

After most of a year working through Tracy’s material, I reached out to him to see if he would be willing to talk with me and answer some questions. There was a conference on his work coming up at Loyola University Chicago, so I returned to my favorite city and met him for coffee and tea in my old neighborhood.

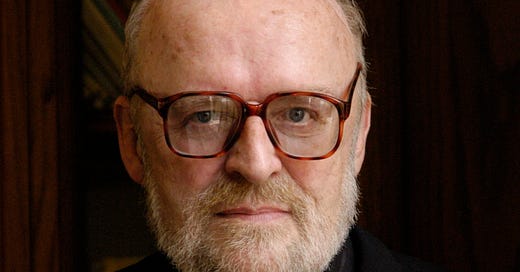

David was probably the most generous theologian I had ever interacted with, a title I think he holds to this day. First, he gave me—a random grad student—almost two hours of his time. He only wrapped our conversation when we did because he had to go up to Loyola to give a lecture and receive an honorary doctorate. Second, he happily responded to the battery of questions I had about his work, such as how he understood human finitude, the shifts in how he wrote about Christ and God, and how he appraised The Analogical Imagination thirty years later.

Third, David had this phrase he often used in talking with people, “as you know.” “As you know, Nietzsche hated Euripides.” “As you know, Rahner was influenced by his encounters with both Heidegger and Kant.” He never said this phrase as a brag about his own knowledge. Rather, I always had this sense in talking with him that he had immense respect for whomever he was conversing with and seemed to just assume that everyone else was intelligent as he was. This was at least how he carried himself.

Fourth, he was always intellectually generous. He read widely and always looked for what was best in another person’s work. You can see this in his many books and articles, where he incorporates the best insights from other thinkers as he develops his own ideas. Part of my argument in my book is that he saw theology as conversation, and was always open to the unexpected directions those conversations might take.

Fifth, he bought my tea that day. When you’re a grad student, every little bit helps.

I took very extensive notes during our conversation, and as a research trip it was incredibly helpful in getting information I needed. But in addition, he modeled for me what theology as conversation could be and the kind of openness I ought to have to other scholars and students whenever I might be of help.

The last time I saw David was in 2019 in Vienna. Andreas Telser and Barnabas Palfrey, two excellent scholars of Tracy’s work, organized a conference at the University of Vienna. I decided to make a whole vacation of it, so my wife Paige and my parents came along.

My fondest memories from that conference were not as much in the papers and Q&A, as great as they were, but in the meals. In those more intimate settings, David was again very kind and engaging. He gave me positive feedback on the book I had written on him, even telling me he had learned about himself from it. He was encouraging of my work on theology and technology, offering his own suggestions of theologians to engage with. For a couple of these meals, my wife was able to join us, and David was unfailingly warm and welcoming to Paige as well.

That conference ultimately resulted in a wonderful volume that Andreas and Barnabas edited. The book was launched at the University of Chicago, with David and some of the authors in attendance. I was regretfully unable to attend in person, watching on Zoom instead. The group from that book, along with several others, continue to meet every month or so to share our research and continue our engagement with Tracy’s theology.

When I was starting to work on my dissertation, one piece of advice Prof. Hinsdale gave was there’s always a risk when writing about a living theologian. Just as you’re concluding your work, they might release something new that you have to account for. To be honest, while writing both my dissertation and my book, I was nervous the “God Book” would finally arrive and I’d have to delay.

The other risk, though, is that the living theologian will pass away. Already mourning Francis, I now mourn David too, even more keenly. It’s not just that I knew David but never met Francis. It’s also that even as Francis is gone, I know there will soon be a new pope. There will never be another David Tracy.

Rest in peace.

David Tracy, The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism (New York: Crossroad, 1981).

For all the possible lack of reverence this blessing included, that Alero lasted far longer than expected, especially through many roadtrips and Chicago and Boston winters I subjected it to.

I'm sad to hear this! I used his work in my own dissertation, and as you know, I relied heavily on your book on his thought to help me get my head around his opus.

May he rest in peace.