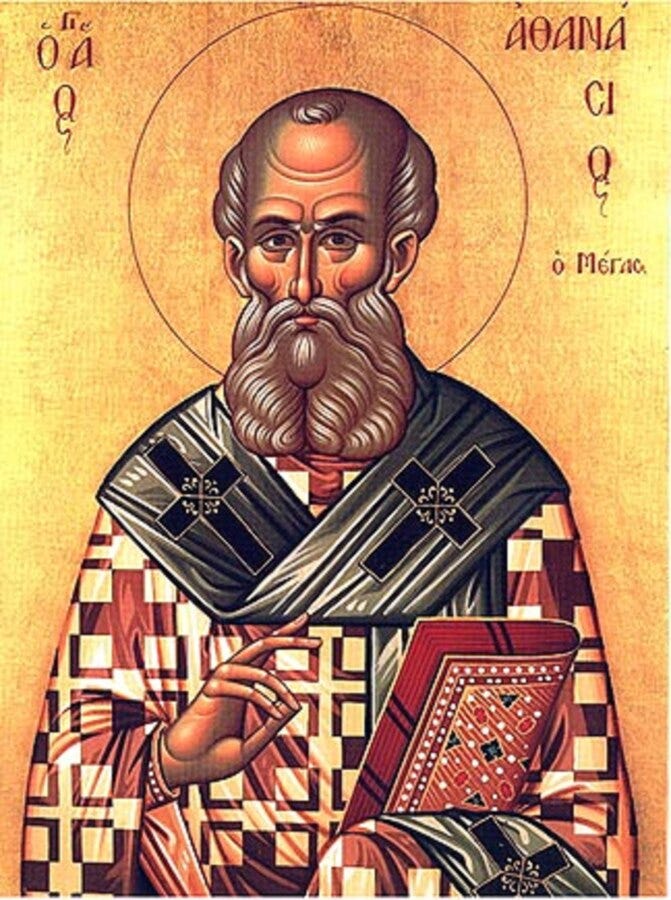

In his On the Incarnation, St. Athanasius of Alexandria deals with the question of why God becomes human in Christ.1 After outlining the doctrines of the Creation and the Fall, he describes the “divine dilemma” - on the one hand, humanity ought to die for its sin, but on the other, something sharing in God’s image should not perish. Through the incarnation, by which God becomes human in the Word made flesh of Jesus Christ, God becomes sensible in a new way to his people (43), offers himself as a sacrifice on behalf of all (49), and destroys the power of death (59). The incarnation is the happy resolution to the divine dilemma.

In a well-known sentence from On the Incarnation, Athanasius writes that “[God], indeed, assumed humanity that we might become God” (54). The idea of divinization or deification presented here has a long and contested history, but at least the central Catholic read on it has been that through Christ’s solidarity with human beings via his human nature, it becomes possible for us to share or participate in Christ’s divine nature.2 Our encounter with Christ can be transformative, and we too can become children of God.

The idea of transformative encounter was perhaps the strongest theme I sensed while watching Denys Arcand’s Jesus of Montreal.

The premise of the film is that the priest of a local shrine has asked Daniel Coulombe, a 30ish actor who is little known and has been away for awhile, to revise and update the church’s somewhat stale passion play. He agrees to do so, assembles a troupe to perform, and does some research to figure out the new script. The performances are well received by some but rejected by the local religious leaders. Escalating tension at the final performance leads to Daniel’s death, but also to a mundane resurrection (through organ donation) and the founding of a new theater to carry on his vision.

The film is not quite a straightforward allegory of the gospels, although there are numerous parallels throughout. The church is replaced by the acting troupe and their theater, centurions are security guards, and obviously Satan is a lawyer. Among the main characters, Daniel is the Jesus figure: he calls fellow actors, teaches them and the crowds, overturns tables (and cameras) in a climactic audition, and later dies. Fellow actor Mireille, the Mary Magdalene of the troupe, is not portrayed as a prostitute (as other films do), but rather as a commercial actress who made a career out of selling sex appeal in advertisements.3

In addition to Mireille, the other interesting character parallel is the Judas character, Fr. Leclerc, the man who asks Daniel to revise the passion play. He is a priest, but not a particularly good one: we learn early on he’s been having an affair with Constance, the first actor to join Daniel’s troupe. He knows he’s a bad priest, saying early on “I’m not a good priest…I tried,” and again towards the end “a bad priest is still a priest.” He is profoundly attached to his identity as a priest, but that attachment is grounded in fear. He worries that if he left, he would have nothing and would be a nobody. He is repeatedly invited by Constance to join her, to join the troupe, to do more than “quietly wait for death,” but he cannot imagine doing so.

His Judas betrayal is thus twofold: not only does he betray the troupe by turning against their revision of the play, but he also betrays himself, his own humanity, by clinging to the comfortable but unfulfilling privileges of his position rather than risking a deeper encounter with God through the call offered to him. Fr. Leclerc in fact is not only the Judas of the film; he is also the Rich Young Man of Matthew 19, called here (by Constance!) to give up his dependence on some worldly security.

Fr. Leclerc’s refusal is a good route to return to the divinization theme I opened this review with. The encounter with Daniel, and with his revised passion play, has a transformative effect on Constance, Mireille, and the other members of the troupe, Martin and Rene. During Mireille’s early days with the troupe, she is upset at Constance’s lack of makeup, resorting to sunglasses to hide how she looks. Her sense of self is still tied to the commercial work she had been doing, which cared only for how she looked.

Later in the film, she goes, out of a sense of obligation, to one final commercial audition. The ad, for a beer, includes dancing and singing, with one of the unsubtle lyrics being “we worship beer.” The audition is run by her ex, who still only sees her as an object, and all the other actors are scantily clad. Mireille, wearing sweatshirt and tights, is reluctant to take her top off (she has on nothing underneath), but is also about ready to do so when Daniel tells her she’s better than this. She is not yet convinced herself, but Daniel overturns the tables and cameras before the audition could continue.

At the end of the film, Mireille (along with Constance) accompanies Daniel in the ambulance to the hospital, and then to the subway, and then to the second hospital. Like the women of the gospels who are present at Christ’s crucifixion, Mireille is a witness and companion to Daniel’s end. After his burial, she is part of the new theater her fellow actors form to carry on Daniel’s ideals of authentic performance. Her encounter with Daniel and his vision of an authentic, un-commercialized theater leads to her own conversion and to her becoming more like Daniel.

Mireille is the most dramatic or most central of the converts, but we see it in the others as well. When Martin is first recruited, he is dubbing the French dialogue for pornographic films. Rene is doing documentary voiceover work rather than pursuing his passion for Shakespeare (he later auditions with the soliloquy from Hamlet, which he later works into the passion play following the crucifixion scene). Fr. Leclerc notes that both of them, along with Mireille, left steady work and careers to follow Daniel, ruining their otherwise good lives, not realizing that they are more really themselves, more fully alive, than they had been before.

In the course of this series, all the preceding films have been explicitly about the life of Jesus, and they’ve done their own versions of telling that story in some vision of first century Galilee, Judea, and so forth. This film transposes the story to contemporary Quebec, and tells the life of Jesus indirectly through (a) a passion play of questionable authenticity and (b) the lives of those touched by the play.

In light of that, this series’ recurring question of “who is Jesus in this film” has perhaps two answers. The technical but unsatisfying answer to (a) is “Jesus is a character written and performed by an actor, Daniel, a character described as probably the bastard son of Mary and a Roman soldier.” Part of the story is Daniel doing research on all the newest ideas about Jesus and incorporating them into his play, some of which are reasonable (depictions of Jesus with and without a beard in the early Church, an explanation of how crucifixion kills), others of which are shakier and more provocative (Jesus was actually just a magician, and he had been dead maybe 5-10 years before reports of the resurrection began circulating). I don’t think this aspect of the film is actually supposed to be satirical; it seems fairly earnest.

However, the more important, more interesting answer to (b) is that Jesus is a figure of such profound commitment and authenticity that those who encounter him and are open to him can have their lives transformed for the better by him. Daniel’s vision of an uncorrupted theater that pursues art for art’s sake, not for commercial gain, is attractive, and he lives in solidarity with his fellow actors (they in fact all end up sharing Constance’s apartment during rehearsal and production).

There is nothing obviously divine in the film: Daniel is an actor, not the incarnate Word of God, and neither he nor anyone else does any miracles. There is a resurrection of sorts, as the film shows patients who benefit from Daniel’s organs after his death, but that’s not the same. Some describe the frequent overhead shots of Montreal as a sort of “God’s eye view” of the city, and maybe this divine POV is the closest the film can get to that aspect.

But any explicit divinity is not the film’s goal. Insofar as there is any transcendence in the film, it is about a conversion from inauthenticity to authenticity. Within the film, inauthenticity is represented by commercialism and materialism while authenticity is art for the sake of the human spirit. It’s a well-meaning humanism, cast in Christian iconography but without Christian commitments.

To be clear, I really enjoyed this movie, and I definitely recommend watching and rewatching it. I think it’s a better and much more interesting movie than The Last Temptation of Christ was. But I also think it is probably attractive to a similar audience as that film, in that it sidesteps and even downplays some of the more challenging aspects of the life of Jesus and of religious belief.

Stray thoughts about Jesus of Montreal:

During the first performance of the passion play, there is a woman who is so convicted by the performance that she kneels down to the actor playing Jesus and begs him to forgive her; the security guard has to pull her back. Later in the same performance, as Jesus is being arrested, she pops back in to yell to Jesus that the men taking him are evil. Honestly I don’t know what to make of this bit, except that she’s one of the only characters in the entire film who seems to wholly buy into her Christian faith. Nearly everyone else is portrayed as more cynical, doubtful, or just not that concerned about the actual claims of Christianity.

During the sequence leading to Daniel’s death, he goes to two hospitals. The first, St. Mark’s, is overrun and poorly managed, and he’s not effectively treated there before leaving. The second, a Jewish hospital, is uncrowded, efficient, and very helpful (even though he’s beyond saving at this point). Some have noted the contrast between the Catholic and Jewish hospital responses, but what stuck out to me more is that in the Jewish hospital, everyone is speaking English rather than French.

An intriguing if subtle example of the shift in the film from a more commercial and institutionalized world to a more “authentic” and less secure one are two unnamed singers. Despite having essentially no direct encounter with Daniel or his troupe, we see them first performing the Stabat Mater in the shrine’s choir loft with a full ensemble during the opening credits, and we next see them performing the same piece, accompanied by a boom box, in the metro station where Daniel collapsed at the very end.

There’s a specific type of story here, where people participating in a passion play see their lives come to be more and more like the Gospel character they perform. The only other example of this I know is Nikos Kazantzakis’ Christ Recrucified from 1954. I’m curious if there are other examples, so let me know if you are aware of any.

Although I opened with Athanasius, I did also consider talking about Irenaeus and the famous paraphrase of “the glory of God is the human being fully alive.” This is often read in terms of authenticity, but I think a lot of those readings miss critical problems in contemporary understandings of authenticity. I don’t agree with all the points Joseph Kim makes here about the quotation, but I think overall he makes a good case.

Next time in the Celluloid Christ series: Last Days in the Desert (2015), directed by Rodrigo Garcia. You can find links to all the posts as they come out in the series page.

I’m using the Popular Patristics edition: Saint Athanasius, On the Incarnation (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimirs Seminary Press, 2012).

Among many other places, you can see this in the Catechism of the Catholic Church 460.

There are many other parallels and references, and I suspect most viewers will catch more and more of these on repeat viewings. Probably the most clever is the head of John the Baptist references; my favorite is the detective who channels the centurion at the crucifixion. During the second performance, Daniel is arrested on the cross, but one of the detectives says to him “I wanted to tell you, I really liked the show. ..Sure makes you think. Sorry to miss the end.” Daniel replies “You can come back.”