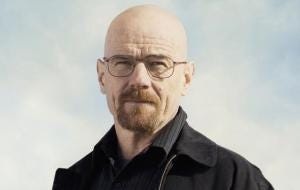

Walter White and the (Im)Possibility of Redemption

**Warning: Spoilers Below!**

By the time I go to bed tonight, there will only be four episodes left of one of my favorite TV shows I’ve ever watched (which is saying something – I’ve watched a lot of excellent TV). One of the few who has watched Breaking Bad since its beginning, I’ve been riveted by the ongoing devolution of its central character, Walter White. I would go so far as to say that not since The Godfather Parts I and II has there been such an excellent study of a decent character whose responses to his circumstances have led him inexorably towards a moral rock bottom.

As a Christian, though, I’ve had one main question in the back of my head these past five seasons: Can Mr. White be redeemed?

Of course, were Mr. White a real human being rather than a fictional one, Christian theology’s response would be an emphatic “yes.” Mr. White would have been created by God and sustained in existence by God’s love. As twisted as he might become, there would still be some fundamental goodness to him. The possibility that he would turn away from his sinful ways and towards love and grace would remain, right up until his end. As unsatisfying as it might be for his brother-in-law Hank or for his many many victims, he would still have a chance at a sincere deathbed confession.

But he’s not real, he’s the fictional center of a narrative about one man’s ongoing moral decline. When the show began, Mr. White seemed like a decent enough fellow: following his cancer diagnosis, he figured that cooking meth would net him enough money to provide for his wife, his son, and his unborn child after he had passed. After he has made his first big drug deal at the end of season 1/beginning of season 2, he calculates that all he needs to provide for his family (the mortgage, college tuition, cost of living), is $737,000. Although Mr. White isn’t a “decent fellow” at that point (he’s already killed and disposed of bodies by then), it’s nonetheless clear that he is “breaking bad” in order to provide for his family.

However, as he gets deeper and deeper into the meth business, he becomes less and less concerned about his family. The whole enterprise centers more and more about his need to feel powerful, respected, feared. When his partner asks him whether they’re in the money business or the meth business, he responds “I’m in the empire business.” The shooting of his brother-in-law Hank is a direct result of Mr. White’s actions.

Eventually, where we are now in the series, there is no one sacred to Walt, no one he won’t lie to or manipulate in order to get what he wants. In last Sunday’s episode, he meets with his erstwhile partner, Jesse, in the desert in an effort to convince Jesse to disappear.

Jesse: Would you just, for once, stop working me?

Walter: What are you talking about?

Jesse: Can you just, uh, stop working me for, like, ten seconds straight? Stop jerking me around?

Walter: Jesse, I am not working you.

Jesse: Yes. Yes, you are. All right? Just drop the whole concerned dad thing and tell me the truth. I mean, you’re– you’re acting like me leaving town is– is all about me and turning over a new leaf, but it’s really– it’s really about you. I mean, you need me gone, ’cause your dickhead brother-in-law is never gonna let up. Just say so. Just ask me for a favor. Just tell me you don’t give a shit about me, and it’s either this– it’s either this or you’ll kill me the same way you killed Mike. I mean, isn’t that what this is all about? Huh? Us meeting way the hell out here? In case I say no? Come on. Just tell me you need this.

Jesse, at long last, begs him to be honest and stop manipulating him. Mr. White responds by walking over to Jesse and hugging him, playing the fatherly role that he perhaps once felt towards Jesse. Now, however, it’s just another ploy to convince Jesse to do what he wants.

Mr. White represents a particularly compelling portrait of the homo curvatus in se: the human being turned in on the self. David Tracy describes the curvatus in se as the self’s “turning in upon itself…in an ever-subtler dialectic of self-delusion…Through that denial, the self alienates itself as well from nature, history, others, and, in the end, from itself” (Plurality and Ambiguity 74). Mr. White has become so profoundly self-centered that he has undermined every meaningful relationship in his life. Even his children, for whom he got himself into this business, are pawns – witness the conversation he has with Walt Jr., where he reveals his recently returned cancer, which is simply an attempt to keep his son away from Hank and Marie.

Series creator Vince Gilligan has described himself as an agnostic, yet he still clings to a commitment to “cosmic justice”: “Because if there is no such thing as cosmic justice, what is the point of being good?” Given his sentiments, it’s hard to imagine the show coming to any conclusion that doesn’t include Mr. White suffering, to some extent, for his crimes. In fact, after the carnage Mr. White has caused, I suspect most viewers see his death as the only ending that would bring both narrative closure and some feeling of justice.

But the impossibility of Mr. White’s redemption is not only a narrative certainty. It’s also a story that tells us something about the Christian understanding of how we ought to live. In becoming so twisted in on himself, Mr. White has risked or destroyed the very lives he once held most dear. Love, understood as one’s willing the good of the other, is not twisted in on itself but directed outwards towards the other. The possibility of Walter White’s redemption would rest on his ability to turn away from himself and towards others, dispositions of which he seems to be incapable. And while the rest of us may not be Nobel Prize-winning methamphetamine kingpins, if we too are unwilling to reorient ourselves towards the other, we too might see the desperation, the alienation, the relational failures that have marked the last few seasons of Mr. White’s life.