The Rhythm of the Would-Be Saints: Pilgrimage as Kairos

It felt like a pebble in my shoe. The sharp pain of something out of place jabbed at me, making me want to take off my shoe and shake it out. But it wasn’t a pebble; it was a cyst in the ball of my foot. After almost three weeks of walking as a pilgrim to Santiago de Compostela, seeking an intense religious experience, I’d developed an injury that made any further steps unbearably painful. I limped towards our stop for the night, Calzadilla de los Hermanillos, unmoved by the ancient stories of pilgrims who intentionally added pebbles to their boots. As I lay in my bunk after dinner, I considered the possibility that I would have to head home, bringing my time as a pilgrim to an end.

The next morning, a taxi took me to the medical center in the next big town, Mansilla de las Mulas. Although I spoke no Spanish and the two doctors spoke no English, they reassured me that my injury was common. They pulled out a needle (larger in my memory than it was in reality), drained the wound, and I was effectively good as new. Following two days of hobbling, one dark evening of the soul, and another day of rest, I could enter back into the rhythm of pilgrimage and continue my journey.

I was walking the Camino de Santiago de Compostela, a pilgrimage that dates to the 9th century. Dozens of routes run across Spain, all converging on the city of Santiago. There, so the story goes, the bones of Saint James, son of Zebedee and apostle of Jesus Christ, were miraculously found by the hermit Pelayo in 813. A shrine was built that drew pilgrims from around Europe. In 1075, building began on the Cathedral of Santiago. In 2014, the year my wife, her best friend, and I made the pilgrimage, more than 200,000 other people did the same: some by foot, others by bike. By the end of our trip, I had logged 1.3 million steps on my Fitbit, had my foot aspirated by a Spanish doctor, and worn down a stout pair of Merrell boots. More importantly, though, I came to have a new awareness of time, and in particular how the rhythm of pilgrimage created a new time and space for my experience of God.

My time as a pilgrim was marked by two rhythms that interwove with one another. First, my two trekking poles (bastones) made a distinctive “clack clack” as I walked. Each step merged the striking of the ground by a pole with the crunching of the dirt by my boot. As the miles wore on in the early morning hours, the sun barely peaking over vineyards and wheat fields, the sounds of my steps were steady enough to set a metronome by. The evenness of the pace kept my body balanced while the poles helped to propel me forward. Indeed, part of how I knew there was a problem with my foot was that the rhythm of my steps changed as I came to favor the right leg. Yet beyond the physical, the clacking of the poles crept into my internal monologue. It became the beat to which I prayed: as I would say an Our Father or a Hail Mary, each “clack” marked a syllable. Prayers that I had said for years gained a new cadence, breaking me free of the mindless repetition that had become my norm. The rhythm of the bastones, as they kept me balanced and moving, gave me new wineskins for old prayers.

Second, my time as a pilgrim brought a new daily rhythm. Each day I woke around 5 am, dressed in the dark, and gathered my gear. I would take some time for footcare (mostly tending blisters), and maybe grab a piece of toast. I would be out the door before 6. I walked all morning, taking occasional breaks to eat an orange or have a drink, until I arrived at the hostel (albergue) for the evening. I’d shower, I’d nap; maybe I’d explore the town for a bit or relax in my bunk. After dinner, I would ready my things for the next day before drifting off to sleep to start again. Walk, eat, shower, sleep. Walk, eat, shower, sleep. Even as each day brought new towns and introduced us to new pilgrims, the basic parts of the day remained the same.

Yet these rhythms did more than order my steps and my days; they opened up new possibilities for encountering the divine. First, they took me out of sync with the routines that had come to typify my life in Florida. I would consider myself a busy person (sometimes for the sake of being busy), and I can grow agitated when I don’t have something to do. All that busy-ness can crowd out opportunities for interiority. On the Camino, I not only had long mornings of walking, but I also had leisurely afternoons and evenings. Once the basics of showering and eating were taken care of, we often had hours of leisure time. There were no pressures to work, to run errands, to be busy; rather, we often spent this time reading for pleasure, relaxing with other pilgrims, or learning the stories of the villages and cities we stayed in. Strange as it may sound, adapting to the amount of free time available was a challenge, but it became an essential and gratifying part of the routine.

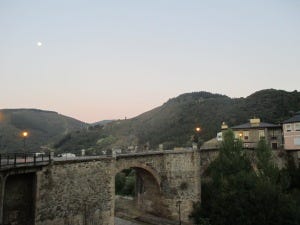

Second, just as I fell out of sync with my usual rhythms, I fell into sync with other pilgrims. Many others were experiencing the same cycle of walk, eat, shower, sleep. Each day I joined other pilgrims by walking, lining up at the albergue for a bed, sharing bottomless bottles of local wine, and exchanging stories of why each of us were walking. I heard stories from people who were transitioning between jobs, or mourning lost spouses, or giving thanks to God for a parent’s recovery from cancer. We supported one another, especially with the challenges of the walk. I recall especially a pilgrim named Hugo from Portugal, who was steadfastly encouraging as I limped around Calzadilla de los Hermonillos. When I saw him a few days later in León, he greeted me warmly and cheered on my recovery.

As the days and weeks passed, I continued to run into many of the same pilgrims. Most of us walked the same distance each day (about 15 miles), but at different speeds. The evenings became small reunions, chances to recount what we had seen that day and to compare how bad our blisters had become. Sometimes we fell behind other pilgrims; an extra day taken at Leon to see the Cathedral, or a rest day due to tendinitis would introduce to a whole new group of pilgrims in the evening. Yet often we would later catch up with pilgrims we had missed, greeting each other like old friends long separated.

Through the combination of exchanging my typical routine for the rhythm of pilgrimage and of coming into sync with other pilgrims, I came to see the Camino as an experience of Kairos. The Greek word Kairos refers to an opportune moment, a time when everything seems to align. Kairos isn’t predictable; it doesn’t come about just because a certain amount of time has elapsed. Rather, Kairos is almost outside of the normal flow of time; it is holy, set apart for divine.

I had decided to walk the Camino precisely because I wanted to dedicate this time to seeking a deeper encounter with God. I sought something of greater intensity than I was experiencing in my local parish and my daily prayers. And on the Camino, I encountered God – or, more accurately, God encountered me – in walking, in prayer, in the landscapes, and in my fellow pilgrims. But this became possible not simply by my wishing it to be so, but by seeing pilgrimage as sacred time. Through a literal change of pace, I was pulled away from the distractions that crowded into the cracks of my daily life and brought into a community of fellow seekers. When injury threatened to pull me prematurely from this Kairos, I became even more aware of how attuned I was to pilgrim time. Simultaneously, as fellow pilgrims assisted and encouraged me, I was brought deeper into sharing that time with others. I was enabled to encounter God by seeing that time as sacred.

And, thanks to my Camino pilgrimage, I am better able to recognize the sacred in other times as well. Even now, I can try to recognize the holiness in my daily routine, setting it apart for God.

Note: this essay was originally published in the Saint Leo School of Arts and Sciences magazine Rebus in Fall of 2017.