The Mission: Choose Your Own Penance

Between high school, college, and my PhD program, I have spent nearly 14 years being formed intellectually and spiritually by Jesuits. Thus it should come as no surprise that Roland Joffe’s The Mission, a moving film about Jesuit missionaries in South America in the middle of the 18th century, holds a special place in my heart. The film deals with many themes: revenge, service, solidarity, redemption, and politics and religion, to name a few. Yet here, given the important role of penance during the season of Lent, I would like to consider the film’s portrayal of penance.

As always, spoilers abound!

Robert De Niro’s character, Captain Rodrigo Mendoza, is introduced early in the film as a slavetrader. He comes to the area above Iguazu Falls and takes a dozen or so of the native Guarani. These are the same indigenous people that Father Gabriel (Jeremy Irons) has come to live with, serve, and evangelize. Mendoza, however, has a troubled home life, and on his return to Asuncion is heartbroken to discover that his lady has fallen for his brother. Mendoza’s impulsive murder of his own brother leads to his rotting in jail for six months, refusing to see anyone. Mendoza wallows in self-pity, effectively waiting for death as he sees no future life for himself.

Father Gabriel visits him and presents an interesting challenge to Mendoza. Despite Mendoza’s claim “For me there is no redemption,” Father Gabriel accuses him of cowardice, both in murdering his brother and in his life since.

Gabriel: “God gave us the burden of freedom. You chose your crime. Do you have the courage to choose your penance?”

Mendoza: “There is no penance hard enough for me”

Gabriel: “But do you dare try it?”

Mendoza: “Do I dare? Do you dare to see it fail?”

This challenge sets up one of the most powerful and grueling scenes of the film. Gabriel, along with by the other Jesuits of the mission, accompanies Mendoza as he climbs up the mountain and the falls to the Guarani mission of San Carlos. Tied to Mendoza is a large netted sack, bursting at the brim with swords, armor, and other weapons, collectively serving as the symbol of Mendoza’s old life. As he climbs, he bears the burden of this life and of the pain it has caused.

In his Confessions, Augustine describes his “sexual habit” as a “weight” that pulls him down, that tears him away from God (Bk. VII, xvii(23)). For Mendoza, the weapons of his former life are quite literally the weight pulling against him as he pursues his penance. And the question of when this weight can be cast off is central to Mendoza’s climb. When the sack gets stuck on undergrowth, one of the Jesuits (played by a young Liam Neeson) hacks it off and lets it fall below. Mendoza climbs below again, reties it, and continues. Not only has Mendoza chosen his penance, but he chooses its completion. In speaking with the other Jesuits, Father Gabriel says Mendoza doesn’t think he’s done, and “until he does, neither do I.”

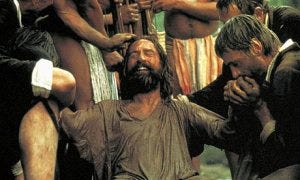

This penance is completed only when the Jesuits and Mendoza arrive at the mission, where the Guarani wait. While greeting the Jesuits with cheers and hugs, there is fear regarding Mendoza. They recall his kidnapping and killing their people. One of the Guarani takes a knife over, shouting at and threatening to kill Mendoza. Though afraid, Mendoza does not react – perhaps still feeling as though he deserves the death he waited for in prison.

Yet the Guarani does not kill Mendoza. Rather, he cuts off the sack and pushes it off a cliff into the river. Outwardly, this is the same act the young Jesuit did during the climb, but inwardly it is entirely different. Mendoza’ penance had nothing to do with the Jesuit, but it had everything to do with the Guarani. Through this act, the Guarani recognize this public act of penance and forgive Mendoza. The weight of his past life is lifted, and Mendoza, perhaps crushed by this realization, weeps profoundly.

The depiction of penance in the film is as complex as it is evocative. The climbing imagery alludes to traditional Catholic views on Purgatory; the heavy burden Mendoza drags up the hill contrasts with and recalls Jesus’ saying “For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Mt 11:30); the three days of his climb parallel Jesus’ own rising again on the third day; and the way the Jesuits accompany him through this process reminds us that penance is not a purely individual act. Rather, we are all members of a variety of communities, and so we are in some sense accountable to and responsible for one another. Part of Mendoza’s penance is that he must forgive himself, which is why he continues his penance so long as he thinks necessary. Yet another part is that he must accept the forgiveness of others, which is why it is ultimately the Guarani who literally relieve him of the burden he was borne.

Through his act of penance, Mendoza is enabled to forgive himself for killing his brother, for enslaving the Guarani, and for the overall violence of his past. He is also enabled to receive forgiveness from the Gaurani. And while he cannot repair his relationship with his brother, he is able to form new familial bonds with the Jesuits of the mission (later becoming on himself) and with the Guarani. The purpose of penance is not to wallow in our guilt and shame, nor is it to punish ourselves for our sins. Rather, it is to return us to communion with our brothers and sisters. It is to release us from the weigh that turns us away from loving God. It is to remind us that, in being called to love our neighbors as ourselves, we must truly love ourselves.