Public Theology and Scientology

The Huffington Post is reporting that Katie Holmes, following the finalization of her divorce from Tom Cruise, is returning to the Catholic Church. First off, in the spirit of Mr. Kotter, I’d like to welcome Katie back to the fold. Second, while the details of their divorce remain confidential, her joining the parish of St. Francis Xavier in NYC and the joint statement’s reference to “beliefs” suggest that Scientology was a significant factor in the breakup. This is not exactly a surprise; rumors have persisted since early in their relationship that faith was an issue for them.

Third, my own interest in Scientology stems largely from its being both very public and very private in an odd sort of way. It is well known that since the 1960’s, the Church of Scientology has actively recruited celebrities for its membership. As such, Scientology has become a somewhat common site of intersection between religion and celebrity. It is a frequent topic in news stories, many of which attest to the intense secrecy that seems to surround many of Scientology’s beliefs.

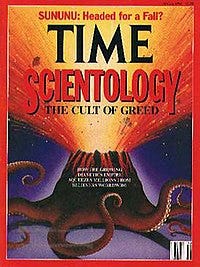

My interest here is to evaluate Scientology in terms of the category of publicness. Scientology is certainly public in the sense that it exercises influence in the public sphere. Time Magazine published one of the first major pieces on Scientology in the 1990’s. Richard Behar (the reporter), the magazine, and Time-Warner itself were promptly sued by the church for libel. While the Church of Scientology lost the legal suit, Janet Reitman has claimed that the time and money involved in the legal bout led to a chilling effect on journalistic efforts to engage Scientology. The Church of Scientology’s resources enabled it to use public, legal means for its defense, but in so doing it was able to shape – and even stifle – public discussion.

This basic sense of the public is not the only relevant one, though. Drawing on David Tracy, we can highlight at least three other characteristics of the public. First, Tracy argues that theology must be public because it deals with fundamental questions that may be asked by anyone. For Tracy, religions are at their core a set of particular responses to particular fundamental questions. Scientology does present itself in this manner, offering an understanding of the human person rooted in the distinction between the reactive and the analytical mind. It claims that auditing can help one to deal with past traumas and fears.

Second, Tracy claims that one of the key marks of publicness is “personal, communal and historical transformation” (AI 55). He writes that claims to truth are grounded in and, in a sense, judged by the ongoing transformation of concrete human lives. This is not to say that person who is not transformed by an encounter with a religious tradition can therefore reject that tradition as untrue. Rather, it means that when one makes claims of religious truth, that truth is witnessed to by an ongoing conversion in his or her life. Transformation witnesses to the truth in religious claims. On a smaller level, Tom Cruise claims Scientology cured his dyslexia while John Travolta and Kelly Preston claim it helped them to heal after the death of their son. More broadly, the church claims that it and its members make real changes in individual lives and their wider communities.

Finally, Tracy says another key mark is “cognitive disclosure” (AI 55). The transformative aspect of truth cannot be separated from the disclosive claims about truth. Put another way, speaking and doing the truth are inextricably intertwined in genuine faith. Largely, I think this is where Scientology has really failed on the question of publicness. Sure, copies of Dianetics, the central text of Scientology, are widely available. However, much of what Scientology teaches (or is alleged to teach) is shrouded in mystery. The church has taken the unusual and innovative step of trademarking its religious materials and suing anyone who makes them publicly available. The basic effort at disclosure, at publicness, is punished severely.

Further, participation in Scientology is reported to be tremendously expensive. The basic practice of Scientologists is called “auditing,” in which one uses a device called an e-meter while being asked questions by a higher level Scientologist. Doing so supposedly helps the audited person to realize blocks in their lives that prevent them from attaining a deeper understanding of themselves. The expenses for auditing and other Scientology classes are notoriously high, even prohibitively so, leading many members of the church into financial distress. The costs might be consistent with those of therapy or counseling, but they seem excessive for participation in a religion.

Thus when viewed through the lens of public theology, Scientology is really problematic. Even if it does respond to fundamental questions and bring about transformation in the lives of its members, it does not allow its members to participate in a public conversation about its claims to truth. It strikes me as gnostic, actually, in that they exercise rigid control over a secret form of knowledge that is only made accessible to an elite group of those able to afford it. Those who leave, if they reveal anything of what they learned in Scientology that is not readily available, are followed, harassed, and publicly pilloried. While I recognize that many of those who speak out against Scientology have agendas of their own, the consistency of reports from many who have left suggests a pattern of treatment of their so-called “apostates.”

In all, I wish Scientology were a more public faith, in terms of openness, dialogue, and engagement. For Tracy, central to being public is being able to make arguments on a variety of levels about one’s tradition that can converse with other faiths, other disciplines, and other cultures. To me, Scientology seems to reject this kind of publicness, keeping its beliefs hidden from view except to those special enough to move deeper into the organization.