The below is a slightly edited version of a talk I gave for a Lenten mission at Saint Leo Abbey a couple years back.

As we walk tentatively through the first days of Lent, some of you might already be struggling under the expectations of a fast. Maybe you gave up something (chocolate, coffee), or committed to doing something extra (morning prayer, a gratitude journal). Myself, I’m giving up soda. So far, so good, but I’m sure the temptation to slip will come. Sometimes it comes early in Lent, sometimes later, but it almost always comes at some point in these forty days.

There is something in that idea of temptation, even on something as comparatively small as a Lenten fast, that deserves a further look. When I walk by the vending machine in my building, most of the time I don’t give it a second thought. I made an offering of its contents this Lent, and that is good to do. But also there might be days when I see the machine and think “soda is good for drinking and quenching the thirst.” Sure, it’s the lowest of stakes, but it highlights that tension between possible goods that is a mark of temptation.

Temptation as a theme for Lenten reflection is itself quite fitting. Our annual Lenten observance over these forty days (Sundays excluded) are a commemoration, a remembering, of the 40 days and 40 nights that Jesus spent fasting. As we know from the Gospels, this period of fasting is the space between the baptism of Jesus by John in the river Jordan and the temptations of Jesus by Satan in the desert.

I think the temptations are often overlooked, maybe seen as only a brief stopover in our thinking about Jesus’ ministry, his miracles, his death, his resurrection. Maybe they’re just a supernatural hazing before his public ministry in Galilee.

I have long been fascinated and frustrated by the story of Jesus’ temptations in the desert, though, and I’d like to suggest for our reflection that the temptations of Jesus play an essential part in the drama of the life of Christ, and that they help reveal to us something fundamental about the universal call to holiness.

In what follows, I’d like first to look at the temptation narratives themselves and put them into their immediate context. Second, I’d like to draw some connections between these narratives and other parts of scripture, both in the Old and New Testaments. Third and finally, I’d like to suggest what I think the temptations of Jesus help us to understand about Jesus’ solidarity with us and what that means for our vocation to holiness.

(1) Narrative and Context

First, some background and context for the story. The temptations of Jesus are presented in the three synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Mark’s version is the shortest, like the plot summary you’d see on Netflix:

At once the Spirit drove him out into the desert,

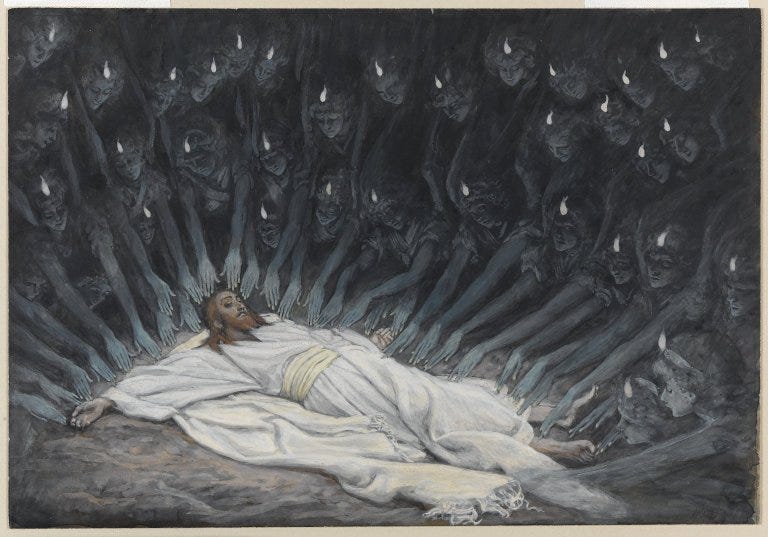

and he remained in the desert for forty days, tempted by Satan. He was among wild beasts, and the angels ministered to him. (Mark 1:12-13)

Despite how spare these verses are, they give us a vital clue to the story. Mark tells us Jesus was driven by the Spirit into the desert. In this way, Mark ties the temptation story to the immediately preceding one, Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan. The very same Spirit that descended like a dove as Jesus arose from the baptismal waters now propels him toward confrontation. Indeed, Matthew and Luke make it more explicit, saying that Jesus “was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tempted by the devil.”1

Next in Mark, following Jesus’ successfully resisting the unnamed temptations, we learn that John the Baptist has been arrested. The end of John’s public ministry gives way to the beginning of Jesus’, who proceeds into Galilee to proclaim the good news.

So Mark gives us a structure for this period of Jesus’ life: baptism, fasting, temptation, public ministry. This structure is shared with Matthew and Luke (with some small changes), but Matthew and Luke go on to flesh out the narrative of temptation itself, describing three specific temptations Jesus faces. Here let us read Luke’s temptation narrative:

Filled with the holy Spirit, Jesus returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit into the desert

for forty days, to be tempted by the devil. He ate nothing during those days, and when they were over he was hungry.The devil said to him, “If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become bread.”

Jesus answered him, “It is written, ‘One does not live by bread alone.’”Then he took him up and showed him all the kingdoms of the world in a single instant.

The devil said to him, “I shall give to you all this power and their glory; for it has been handed over to me, and I may give it to whomever I wish.

All this will be yours, if you worship me.”

Jesus said to him in reply, “It is written: ‘You shall worship the Lord, your God, and him alone shall you serve.’”Then he led him to Jerusalem, made him stand on the parapet of the temple, and said to him, “If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here,

for it is written: ‘He will command his angels concerning you, to guard you,’

and: ‘With their hands they will support you, lest you dash your foot against a stone.’”

Jesus said to him in reply, “It also says, ‘You shall not put the Lord, your God, to the test.’”2When the devil had finished every temptation, he departed from him for a time.

So in Luke we hear that the three temptations are first, to turn stones into bread; second, to worship Satan and thus receive all the kingdoms of the world; and third, to throw himself down from the top of the Temple and let the angels catch him.3

But what else do we hear in these three temptations? Each time that Jesus is presented with some option by the devil, Jesus’ response is grounded in scripture. He quotes Deuteronomy three distinct times, embodying 8:3’s claim that “it is not by bread alone that people live, but by all that comes forth from the mouth of the LORD.” Despite his hunger, despite the goodness of bread, Jesus is sustained here by relying on the higher good that is the word of God.

Perhaps Jesus’ reliance on the word throughout the first two temptations in Luke nudges the devil to try quoting scripture himself. Satan references Psalm 91, telling Jesus that nothing bad would come of throwing himself from the Temple. Looking to the fuller passage from Psalm 91, though, shows already how Satan quotes scripture in order to twist scripture:

“Because you have the LORD for your refuge

and have made the Most High your stronghold,

No evil shall befall you,

no affliction come near your tent.

For he commands his angels with regard to you,

to guard you wherever you go.

With their hands they shall support you,

lest you strike your foot against a stone.

You can tread upon the asp and the viper,

trample the lion and the dragon.” (Psalm 91:9-13)

Jesus is already protected by the Lord his refuge; there is no point in testing it out. Satan’s use of Psalm 91 deliberately undermines the meaning of Psalm 91, something Jesus surely recognizes in rejecting this final temptation in Luke chapter 4. The devil’s quoting scripture here is a partial truth, and one meant to deceive.

(2) Temptations Across Scripture

Jesus’ own reliance on scripture in the temptation narratives give us an interpretive suggestion for understanding the temptations. The theme of temptation is not unique to these passages, but rather is one we have seen across both Old and New Testaments.

For instance, the conclusion of Luke’s temptation narrative contains a phrase unique to his Gospel. He concludes with the ominous line “When the devil had finished every temptation, he departed from him for a time.” For a time! These temptations may be over, but temptation itself is not.

Later in Luke, there are two main places that “for a time” might point us to. Many commentators link this statement to Luke 22:3, when “Satan entered into Judas” and Judas went to make a deal with the chief priests and temple guards. This is a return of Satan as an agent in the story, so that makes sense.

Later on in Luke 22, Jesus withdraws to pray, telling his followers “pray that you may not undergo the test” (Luke 22:40). The word in Greek here, peirasmon, is the same word we translate as temptation in Luke 4. After saying this, we come to the famous “Agony in the Garden” story, where Jesus prays to the Father, floating the possibility that the cup might be taken away from him before accepting it as God’s will. On returning to his disciples, Jesus again says to them “pray that you may not undergo the test,” (Luke 22:46). I think these bookends suggest that the Agony in the Garden is itself the test, and perhaps that Jesus has had a fourth temptation.

We hear that line, “pray that you may not undergo the test,” in Matthew in a slightly different form. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus teaches us to pray with the Our Father. The penultimate clause of this prayer is “lead us not into temptation,” a prayer that is all the more striking when we remember that it was the Spirit that led Jesus into temptation.4 Jesus’ exhortation to pray that we may not undergo the test expresses the spiritual insight of an older brother who has already been where you are traveling and tells you not to go. He is, as Hebrews tells us, “one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin” (Hebrews 4:15).

Temptation runs almost like a throughline in these three gospels, revealing something important about Jesus’ human experience. It also points us to think about temptation elsewhere in scripture, to see who else has had the misfortune of undergoing the test.

We recall the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden. After being given one simple rule for a blissful life in Eden, Eve is tempted by the serpent to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. She is told a partial truth by the serpent - that eating of the tree would make her and Adam like God - and she sees that the fruit is good to eat. Through this temptation, the arc of human existence changes, cracked in its very foundations.

Later in Genesis, Abraham, an aged father promised descendants as numerous as the stars of the sky, is tested by the call to sacrifice the very son through whom those promised descendants were to come. Abraham does not hesitate to set off on his journey, even as he dances around Isaac’s questions. It is only as he nears striking the fatal blow that this test comes to an end, as Isaac is spared and Abraham is acclaimed for his fidelity to the Lord.

Elsewhere, the upright and prosperous Job is tested. Satan appears here as well, claiming that Job’s righteousness is merely a side effect of God’s provision for Job. Take away his wealth, his family, even his health, and Job will turn. And so God allows all these to be taken away. As Job sits in a pile of ashes, scraping himself with pieces from a broken pot, even his wife tells him to “curse God and die,” to choose the comfort of the grave over the anguish of this life. Job calls on God to account, rejecting his friends’ assertions that Job’s suffering must be his own fault. In the end, even as God puts Job in his place, God also tells the friends that Job has spoken rightly of him. The test passed, God restores Job.

The various stories bring us back to an earlier question: what does it mean to be tempted? What is the reality of such tests? These stories from scripture are truly life and death; the stakes are far higher than me and my Coke Cherry Zero.

First, we must recall that in temptation there are the pulls of distinct possibilities. Temptation is a dilemma, an opportunity to depart from one path for another. Eve, Abraham, Job, and Jesus: each are on some trajectory in relation to God, and each are offered opportunities to depart from that path.

Second, and this is key, that offered alternative is desirable and seemingly good:

Eve saw that the fruit of the tree was good to eat

We know that Abraham deeply loved this son of his old age, and despite his lack of hesitation we can imagine he might also have wanted to protect that son

We can see that all the main characters in Job see the good in an end to his suffering: for his wife it will come through death; with his friends through confession of his presumed transgressions; for Job, it can only come from God.

With Jesus, of course we can see the good of food when one is hungry, of making good use of one’s power to help others, or of finding comfort in the safety and protection afforded by God.

None of our temptation narratives are about being drawn to evil for the sake of evil. Temptations are generally subtler than this. Temptations always draw us towards some kind of goods.

Third, specifically in those temptations that feature Satan, the adversary, we see partial truths:

Eve is told that she will be like gods, knowing good and evil. Later in Genesis 3 “the LORD God said: See! The man has become like one of us, knowing good and evil,” just before banishing them from Eden (Gen 3:22-3).

With Job, God seems to acknowledge that Job has in fact had his protection by then allowing Satan to do as he pleases with Job.

And, as we saw, even with Jesus Satan uses scripture about divine protection as part of the third temptation in Luke.

(3) Temptation, Solidarity, and Holiness

So in temptation, we face an opportunity to choose between two or more paths, and we see the possible goods of those paths. We may even be deceived by others, or by ourselves, about those goods. But with temptations, one or more of those alternative paths are wrong, or wrong for us, or will lead us away from the life of holiness God calls us to.

Adam and Eve are pulled from their mission to till and keep the garden

Abraham in his test, had he failed, would have been pulled from a vocation that demonstrates his faithfulness to God first and foremost

Job would have been pulled away from his accurate and authentic naming of God

Jesus, more to the point, would have been pulled away from his mission of salvation, from his fundamental existence of union with the Father

In this last one, we return to a central point: Jesus went into the desert to be tempted. His temptations were real temptations, not Docetic performances for our benefit. Again, he is the “one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin.” St. Athanasius writes that in the Incarnation, the Word takes “to Himself a body, a human body even as our own,” such that Christ is in “solidarity” with humanity and “the corruption which goes with death [loses] its power over all.”5 Amid his solidarity with us, he experiences temptation, showing that being tempted is not sinful, merely human. Temptation is a painful part of our discernment of the call to holiness.

In light of all that I’ve said, what does discerning one’s vocation look like? Must you be suspicious of every possible good option presented to you, fearing that Satan lurks behind each one? No, I don’t think so. What ties together the stories of resisting temptation and of passing the test is clinging to God. Or, to put it better, it is recognizing that whatever particular form one’s call in life takes, the heart of that call is holiness, of living a life that is set apart for God.

For each of us, the specifics of how we live that vocation to holiness differ. Some of us are called to holiness through marriage, or religious life, or neither. Some of us are called to be lawyers, or nurses, or athletes, or (God help you) theologians. Again, look back to our forebears in scripture: Abraham and Job were married and had children; Jesus did neither. Job was incredibly wealthy; Jesus was born in a manger. Jesus was a carpenter; Abraham and Job weren’t.

Yet each of them, and each of us, are called to holiness. And these tests, these temptations, some of them really are challenges to that fundamental vocation, the one that animates whatever the particulars of our life look like. While I don’t think the soda temptation I’ll face in the coming weeks is on that level, maybe the discipline, the freedom, of saying no to that will aid me when the tests take on higher stakes.

More importantly, Jesus shares in our experience of temptation; he understands that possibility of living a life less holy, even though it is a life he would never ultimately choose. He exhorts us to prayer so that we might evade temptation. He models for us the clinging to God that can sustain us through temptation. And his solidarity with us can also give us the strength, the wisdom, and the grace to stay on the path to holiness.

Thanks for reading. I hope to offer some more scripture reflections during this season, so let me know what you think in the comments.

Emphasis added

See also 1 Cor 10:9, “Let us not test Christ as some of them did, and suffered death by serpents.”

The order of the last two temptations is inverted in Matthew; no one is quite sure why there is this difference between the two gospels or which ordering is the original.

Although it must be pointed out these are different verbs in Greek: in Matthew 4:1, it’s anēchthē, while in Matthew 6:13, it’s eisenenkēs.

Athanasius, On the Incarnation, sections 8 and 9 (this translation is from St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation, trans. A Religious of CSMV (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1996), 34-35).