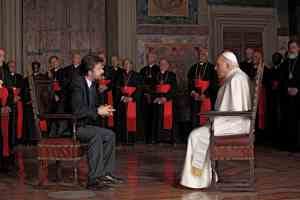

Nanni Moretti’s “We Have a Pope”

I have been meaning to see Nanni Moretti’s film We Have a Pope ever since I first saw the trailer a year or so ago. The basic premise of the film is that a cardinal, on being elected pope, has a nervous breakdown before being introduced to the crowds in St. Peter’s Square. The Vatican then brings in a psychiatrist (who happens to be an atheist) to try and help him. This setup provides ample opportunity for the film to interweave humor, joy, fragility, hope, and finitude into a sometimes coherent, sometimes frustrating tale. In light of the changes going on in the papacy these days, I thought it high time I got around to seeing this movie (BTW: it is currently streaming on Netflix).

Warning. Spoilers below.

The film opens with scenes that will become familiar to us over the coming weeks: the conclave that follows the end of a papacy. The portrayal is, as best I can tell, quite accurate. The cardinals file into the Sistine Chapel, dutifully ignoring reporters while chanting a litany requesting prayers. Once inside, the inner prayers of the cardinals – “please, not me” – is provided in voiceover in a wide array of languages. There is voting, there is counting, there is some small group politicking, and there is general tedium and frustration as the process goes on for several ballots. While the frontrunners do well in the early rounds, eventually an unexpected candidate – Cardinal Melville – emerges with sufficient votes. As it becomes clear that he will win, cardinals turn toward him and clap, looks of genuine excitement on their face.

His face, however, tells a different story. At times looking touched by the respect of his colleagues and humbled at the task asked of him, overall he shows a growing terror. Like the others, he had prayed not to be selected, and now does not know what to do. When asked “Do you accept” by another cardinal, the question must be repeated before he can blurt out his “yes.” Following a whirlwind of being dressed for the balcony presentation and the public declaration “Habemus Papam!” the new pope screams in terror, runs away from the other cardinals, and returns to the voting room to put his head down. Shock is evident, both among the cardinals themselves and the faithful outside in the square. While those gathered in the square did not hear Melville’s screams, they are clearly confused as to why the traditional declaration has not been followed by a public introduction.

Cardinal Melville’s response is understandable. He is told at one point that “a billion people are waiting for you,” putting an accurate but still oppressive number on the enormity of what he’s being asked to do. He had also not expected it – later in the movie, the gambling odds on his election are said to have been 90 to 1. Despite the dean of the College of Cardinals telling him that God will help him to be pope, Melville will later tell the psychiatrist that “God sees abilities in me I don’t have.” While in some movies this admission might lead to Burgess Meredith, Charles S. Dutton, or Viggo Mortensen giving a pep talk about digging deep or seeing their true talents, here it serves as Melville’s frank recognition of his own limitations.

Much of the film takes place with the newly elected pope escaping into Rome and being on his own. Taken secretly by the Vatican spokesman to see a second psychiatrist, the pope gives him the slip and encounters shopkeepers, street musicians, and actors while dressed as a normal civilian and giving away no hint of who he is. He speaks to strangers on a bus about how “recently it’s been hard for the Church to understand things” and that they are “afraid to admit our faults,” but most look on him with pity. Just a lonely or crazy old man. During his absence Melville eventually goes to a poorly-attended mass where the priest preaches on the importance of humility and how only God can heal our wounds. Again, rather than being received as a pep talk, Melville is inspired to meet with the Vatican spokesman and ask simply that he be allowed to go away, to disappear, and to have another cardinal take his place as pope.

The film is really effective in highlighting Cardinal Melville’s sense of his own fragility and finitude. Rather than using common film tropes of an underdog rising to success in an unexpected situation, it shows the real and ponderous weight placed upon someone called to lead a massive international congregation. Melville does not think himself capable of leading the church effectively. He says “so many things need to be changed,” but he cannot see himself as the person to do that. Even when he finally makes it out to the balcony to be introduced to the people, he claims that although the Lord chose him, he finds that this choice “crushes me, confuses me.” In the days between his election and his introduction, the Vatican claimed he had retired to his apartments to pray in humility over this great task; he himself admits, however, that it is a task he is not up to. He asks for the prayers of the people, but also their forgiveness as he says he cannot be the one to lead the church.

When this film was made only a couple years ago, it was hard to imagine anything but death ending a papacy. Even when Melville is asked if he accepts, it comes across as a formality, and he gives the only possible answer. The shock of his public refusal to be pope is evident in the distraught faces of the cardinals and the shocked look of the faithful in the square. Now, as the weight of custom shifts with Benedict’s resignation, it seems possible to imagine Cardinals unwilling to serve using the threat of resignation to prevent their own election. Yet it is also possible to imagine a greater willingness to serve in the office of the papacy now that it no longer need be seen as a death sentence as well.

While I’ve focused here on the main thread of the film – Melville’s long and nuanced reflection on his own life – there are other elements worth noting. One is the screwball comedy wrought by the Vatican spokesman, whose schemes to keep the public (and even the cardinals) in the dark about what is truly going on grow increasingly absurd (culminating in a member of the Swiss Guard dressing in white and playing the decoy in the Papal apartment). The second is the atheist psychiatrist who, now locked up with the cardinals (since the conclave is not technically over), devises a round robin volleyball tournament among the cardinals. Placed into teams by continent (with Europe getting an A and a B squad), this part of the film is really joyous and life-giving, as you see the glee on the faces of the cardinals playing and of the guards, sisters, brothers, and priests who watch in the courtyard. When the three cardinals from Oceania – the smallest team in the tourney – finally score a single point, all join in their elation. While these elements are wonderful on their own, the film ultimately suffers from what I call “Ang Lee syndrome” – tonally, there are too many movies going on at once to really have a coherent whole.

In the end, the film’s beautiful portrayal of Cardinal Melville is a powerful and helpful reminder of our own finitude, as well as that of those in leadership positions in the church. As Kat Greiner has so beautifully said, we need to “to embrace our own human finitude and let go of our need to be in control. This surrender helps us find our own “spiritual freedom” and this freedom allows us to love God, others, and ourselves more attentively and intentionally. “

As a final note, this marks the first in a series of weekly posts during Lent on films with important theological themes. The remaining films will focus on various Lenten themes and, like this one, will no doubt contain spoilers.