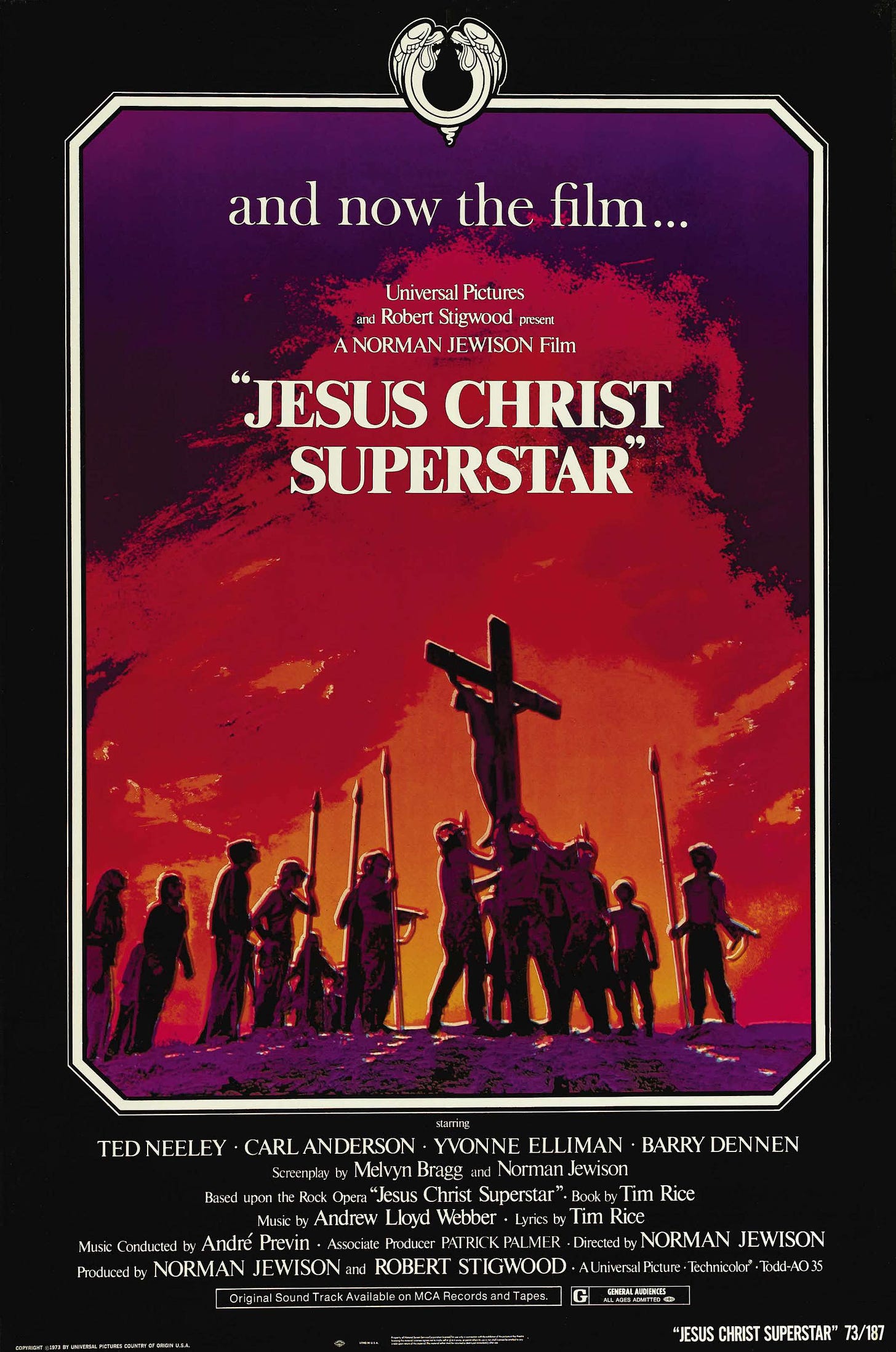

Jesus Christ Superstar: Who Do You Say I Am?

For me, the staple film of Holy Week is Jesus Christ Superstar. The first time I saw the film was in high school when VH1 was airing it on Palm Sunday. Being an early 1970’s rock opera, the movie seemed to be pure cheese to me. But the music was catchy, so I kept watching, and by the time Herod’s scene came, I was hooked. In fact, my senior year of high school, I tried to convince the woman who ran theater at my high school to let us do Jesus Christ Superstar because I wanted to play Herod (unfortunately, we ended up doing Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and I had to settle for Naphtali).

More recently, I have used the film in my intro theology course. What strikes me now about the film is the way it plays with the question of who Jesus is. In the Synoptic Gospels, while traveling with his disciples, Jesus asks them about how they understand his identity:

Jesus went on with his disciples to the villages of Caesarea Philippi; and on the way he asked his disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” And they answered him, “John the Baptist; and others, Elijah; and still others, one of the prophets.” He asked them, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter answered him, “You are the Messiah.” And he sternly ordered them not to tell anyone about him.

(Mark 8:27-30; cf. Mt 16:13-16, Lk 9:18-20)

Jesus Christ Superstar never asks this question in quite the same way, but the question is nonetheless at the heart of the film. In her main song, Mary Magdalene sings

I don’t know how to take this

I don’t see why he moves me

He’s a man

He’s just a man

Just before his death, Judas sings similar words:

I don’t know how to love him

I don’t know why he moves me

He’s a man

He’s just a man

He’s not a king

He’s just the same

As anyone I know

He scares me so!

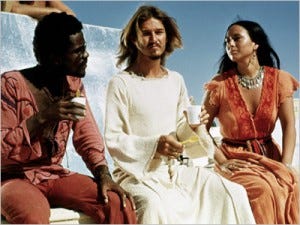

In both cases, they recognize that Jesus “moves” them, that he even scares them. Yet both Mary and Judas want to say that he’s just a man, that there’s nothing obviously special about him…except the effect he has on them. In the film, they sing “he’s just a man” in such a way that they don’t seem convinced, recognizing that even if he is just a man, he’s not a man like any other.

In the title track, Judas wants to know whether the coming of Jesus worked out the way it was intended, asking

Now why’d you choose such a backward time

And such a strange land?

If you’d come today

You could have reached the whole nation

Israel in 4 BC had no mass communication

and

Did you mean to die like that?

Was that a mistake or

Did you know your messy death

Would be a record breaker?

But what I see as the really interesting part of this song is the chorus. The first part of the chorus asks “Who are you? What have you sacrificed?” This is followed by “Do you think you’re what they say you are?”

These lines take Jesus’ questions to his disciples and invert them. Rather than asking what others say and believe about Jesus, it asks Jesus whether he believes what they say about him. It asks whether his coming went the way it was supposed to, whether the prophesies were really fulfilled, and whether his sacrifice was worth it. And when the chorus and Judas’ lines are put together, the real question seems to become whether this divine plan was the best way to spread the message.

The purpose of this inversion is not to get an answer out of Jesus, and the film never really pretends this is possible. Rather, what it does is drive us to think about these questions in a new way. In part, we are tasked with the perennial question of “who do we say Jesus is?” Is he just a projection of my own wishes and desires, my “own personal Jesus”? Or is he the savior and liberator who challenges me in my complacency, who mediates Gods’ grace to me as both “gift and threat” (to quote David Tracy)?

And in another part, I think we are tasked with thinking about how we help to spread the message of God’s love for creation. The other day I posted a quote from Oscar Romero about how we as the Church are God’s microphone on earth. We are the ones called to lives of holiness, to loving God, our neighbor, and ourselves. Judas is right that mass communications didn’t exist in Jesus’ time, and yes there is much good that can come from working with the many gifts that modern technology has blessed us with. But the fundamental medium is ourselves. “At its most profound level, [communication] is the giving of self in love” (Communio et Progressio 11).

As we approach the Triduum and look forward to celebrating the resurrection, I hope we can reflect on Christ’s communication of himself to creation, and how we in turn can communicate that to one another.