Heaven on Their Minds: Salvation, Commodity, and Relationship

I should probably begin by making a confession (we are talking about the afterlife, after all). The question of salvation has not been a big one in my life. I haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about where we will go, where I will go, after death. And that’s true both of my spiritual life and of my research.

So it has been an unexpected blessing this past semester that the courses I’ve been teaching have brought the question of salvation front and center for me.

First, and most obviously, I’ve been teaching a course on the history of Christian teachings about salvation. We’ve read extensively from Augustine, Aquinas, and Calvin, and going forward we’ll look at the Joint Declaration on Justification, Gaudium et Spes, and Hans Urs von Balthasar. Teaching this course has been a fascinating experience. By way of demographics, I teach at a Catholic university at which only about 1/3 of the students are Catholic. Within the classroom in question, I would say there are definitely sizable blocks of Catholics and evangelical Protestants (with the remaining students, I haven’t noticed anything that would mark them as members of any particular religious tradition). The faith commitments of these two broad traditions have often come to the fore in class.

Concurrently, the anxiety many students seem to feel about the question of salvation comes out in class too.

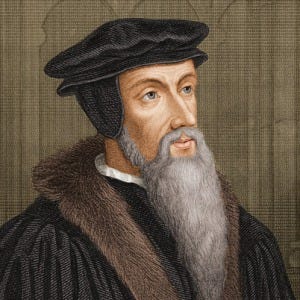

This came out most pronouncedly when we were reading Calvin. Usually when we think of predestination, I think we have Calvin in mind. For Calvin, God predestines who will be saved (the elect) even before their creation, and this election is not rooted in God’s foreknowledge of what we will do with our lives. In that respect, Calvin has a lot in common with Augustine, whom he self-consciously appropriates, and even Aquinas. Calvin, however, goes a step further than either, claiming that God also predestines who will be condemned (the reprobate) (for Augustine and Aquinas, those who fall away choose on their own to fall away). Calvin says that we ought not to seek any cause of predestination outside of God’s will, effectively severing the question of salvation from how we live our lives.

Reactions to Calvin on this tend to vary: some find it horrifying (one student described Calvin’s God as a monster) while others find it liberating (it’s so completely out of one’s control that there’s no point worrying). Some students find it as obviously true as others find it obviously false.

What I found most striking, however, is how many students were bothered by this not because of the vision of God it offered but because of the loss of a feeling of control. When salvation is tied to our actions, as frightening as a divine judge might be, we can also imagine a human sense of justice where one gets what one deserves. Person A lived a good life, so it’s fitting they get into heaven; Person B was an unrepentant sinner, so they deserve punishment. In either case, they made their own decisions, so they were in charge of their fate.

While I think Calvin’s understanding of salvation is too extreme, it does highlight some of the problems with a “control” mentality in salvation. That sense of control profoundly ignores the role of grace in salvation. Grace as a gift is not something that we deserve or have any right to. Salvation is intimately tied up with this gift.

To better explain what I mean here, I should mention another course I teach, ethics, where salvation has come up somewhat more tangentially. There, we read John Kavanaugh’s Following Christ in a Consumer Society, where he identifies two general ways of living in the world: the commodity form and the personal form. By commodity form, he means that we treat others and our relationships as commodities that can obtained, used, and disposed of with little to no commitment. We see persons as objects, not subjects. In that way of life, the dominant question seems always to be “what am I getting out of this?”

The personal form focuses on seeing the other as really, fully human. It means making commitments to others, building relationships with them, and seeing them for their innate worth and dignity. According to Kavanaugh, the “consumer society” of the title is an often unconscious program of social and cultural formation that trains us to live according to the commodity form, while the Gospel calls us to resist this and live according to the personal form.

Where these two different trends come together is in whether we let the commodity form or personal form shape our understanding of the afterlife. Are heaven and hell to be viewed as commodities that we earn or deserve? Do I try to live a good and moral existence in this life solely or primarily to purchase a ticket into the next one?

I don’t think so. St. Thomas Aquinas describes the supernatural end of human existence as “life eternal, that consists in seeing God” (ST I.23.1). The fact that it is eternal life with God seems crucial: we are meant for an eternal relationship. Our hope for the next life is to see “face to face” (1 Cor. 13:12). Not because we feel as though we’ve earned or deserve it, but because of the person we want to be with.

Grace is a gift, and it is God’s initiative that gives this gift to us. The grace that heals our wounded nature enables us to freely respond to God’s gift of grace. Yet that response ought not to be construed as an act of control, as something earned, or as a commodity to be possessed. Grace expresses and enacts God’s desire to be with us; our response ought to be one of gratitude for and openness to that relationship. Salvation should not be about the bliss we hope to attain, but living fully in the relationship that establishes that bliss.

In your classes or ministries, have you spent much time discussing salvation?

How have encountered a “control” mentality regarding salvation?

Have you encountered much anxiety regarding salvation?