Five Responses to Job’s Suffering

For to me sighing comes more readily than food;

my groans well forth like water.

For what I feared overtakes me;

what I dreaded comes upon me.

I have no peace nor ease;

I have no rest, for trouble has come!

– Job 3:24-26

A few weeks ago, I volunteered to write on the Book of Job for this year’s Vacation Bible School. I have long loved and been challenged by the text, and I looked forward to reading it in light of politics and the family.

The story of Job is one that many turn to in times of suffering. The upright and blameless man becomes the subject of a bet in the divine court between God and the adversary. God allows Job to fall into the adversary’s hands, who successively takes away Job’s property, his family, and his health. In this way, it is a universal story, as all have suffered loss that is unexpected and inexplicable.

Friends arrive, apparently to comfort Job, but then also to harangue him. Job’s friends are not privy to the conversation in the divine court, so they don’t know that God has put Job into the adversary’s hands. They don’t know that Job is cosmically recognized as a scrupulously good person. They don’t know that his trials come down to, essentially a bet. Job doesn’t know that last part either, and that catalyzes his chapters and chapters of righteous and holy questioning.

Sadly, reading Job has proven timely, given the terrifying events of the past week in Baton Rouge, LA, Falcon Heights, MN, and Dallas, TX. My thinking on the killings of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and the five police officers in Dallas has been shaped by my reading of Job’s suffering, and even moreso by the responses to him. Looking at how others act in light of his profound losses has made me wonder about my own reaction and response to unjust suffering in the US. As I see it, Job’s suffering elicits five distinct responses throughout the course of the text. These responses may help us, or at least me, in thinking about the call to respond to the suffering of others.

(1) “Curse God and die!” (2:9)

Job’s wife, seeing the extremity of his loss (and, presumably, hers as well), tells him to give up. Don’t hold on to your alleged innocence, curse the God who has either afflicted you (or allowed you to be afflicted), and die. What I find most compelling here, though, is that the text does not equate “cursing God” with “questioning God” or even “challenging God.” For all of Job’s speech, for all of his frustration, for all of his calling God to account, he never curses God, rejects God, or turns away from God. Indeed, the text even says that “Through all this, Job did not sin in what he said” (2:10). Questioning God does not signify a lack of faith but rather a deep commitment to faith.

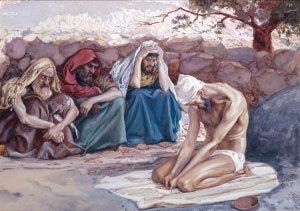

(2) “Then they sat down upon the ground with him seven days and seven nights, but none of them spoke a word to him” (2:13)

Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar have heard of Job’s suffering and have come to comfort him. Their immediate responses on encountering him are weeping, throwing dust over their heads (an expression of mourning – see Lamentations 2:10), and sitting silently with him. They spend a week, seven days and seven nights being a silent presence to him in his suffering. There are no questions, no explanations, no awkward jokes, no words. They are, as best as they are able, sitting in solidarity with him in his pain.

(3) “As I see it, those who plow mischief and sow trouble will reap them.” (4:8)

The majority of the Book of Job, chapters 3-31, are composed of a series of speeches by Job and his three friends (and 32-37 continues with more speeches, now given by the previously unmentioned Elihu). These speeches largely pivot on Job’s expression of frustration and questioning of his suffering and his respondents essentially saying “you must have done something to deserve this.” These same friends who sat a week with Job now claim that “such is the place of the one who does not know God!” (18:21) and “Is not your wickedness great, your iniquity endless?” (22:5). The response here given to Job’s suffering is essentially “You brought this on yourself.” In the case of Job, the prologue lets us know that this is false (not that Job’s friends were privy to that conversation). Beyond the particularity of Job, though, the pastoral strategy of blaming the victim is unproductive at best and genuinely cruel at worst.

(4) “Have you comprehended the breadth of the earth? Tell me, if you know it all.” (38:14)

Job’s speeches often call on God to answer, and beginning in chapter 38 God does so. The famous “voice out of the whirlwind” largely questions Job in return, challenging Job’s understanding of how things ought to be. In particular, God asks whether Job was there at the creation of the world, whether he is responsible for the animals of the earth, and whether he would undermine God’s ordering of the universe. In this response, God takes the role Job had for himself, saying “I will question you, and you tell me the answers” (38:3, 40:7). In so doing, God effectively tells Job that he not only does not understand his own (just?) suffering, but that he cannot understand that suffering, so don’t seek to understand that suffering. Life is unfair in human terms, so deal with it. Some readers take this as the strange fruit of Job’s earlier “We accept good things from God; should we not accept evil?” (2:10).

(5) “The LORD also restored the prosperity of Job…the LORD even gave to Job twice as much as he had before.” (42:10)

In the end, however, God will say that Job has in fact spoken rightly about God and the friends have been mistaken. God refurbishes Job’s wealth, doubling the flocks and herds taken from Job in chapter 1 (apparently consistent with the “twofold restitution” associated with theft in Exodus 22:3). In terms of family, Job has seven new sons and three new daughters, a somewhat awkward passage that skirts over the irreplaceable loss of one’s family. In this epilogue, God seeks to restore Job, both to his prosperity (minus his slaves) and to his community.

As best I can see, it is a holy thing when humans respond to their own suffering with questions, with beseeching, with a search for answers. Like in so many of the Psalms, it’s a profound expression of a faith whose hedge of divine protection has been replaced by a siege of sorrow (Job 1:9).

In being with those who suffer, I believe the holy thing is to respond as Job’s friends did initially – with presence and solidarity – and as God did in the end – participating in the restoration of those who suffer. Doing so in light of recent events requires listening to the stories of those who suffer and hearing from them what they need. I don’t always know the best way to do this, to enact solidarity with oppressed and marginalized neighbors and to be present to grieving families. At root, though, it’s not about a particular technique, but rather a conversion of heart. And based on my meager actions, occasional hashtag activism, and general discomfort with controversy, I can’t say that my heart has fully been converted.

On the other hand, some responses to these situations prefer to tell people that they aren’t suffering, that their suffering is their own fault, or that suffering is simply their lot in life. These seem like something from Job’s friends or the whirlwind, and they can exacerbate the personal chaos and prolong the isolation of the grieving. It may simply be a defensive response, shifting responsibility to the sufferer rather than recognizing my responsibility for the one who suffers. I think this is part of the negative reaction so many have to #BlackLivesMatter – it places a claim, a command really, on us. Not just on those who directly cause suffering or who benefit from suffering, but even those who at first seem tangential to that suffering. Maybe for some Christians, saying #BlackNeighborsMatter would be more jarring, particularly in light of this past Sunday’s readings (and I highly recommend Sam Sawyer, SJ’s excellent interpretation of it). Maybe that would remind all of us that, while everyone might be our neighbor, the true expression of neighborliness is responding in mercy to the one in need.

To paraphrase, saying Job’s life matters is not to deny that Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar’s lives do too. It’s to recognize that in this situation, Job’s life is the one in need of our focus. We must respond in solidarity to his suffering.