Cooperating with the Lesser of Two Evils

There are some voters out there who are passionately in favor of Hillary Clinton, and there are some who are passionately in favor of Donald Trump. However, polls seem to show that a higher percentage of voters are displeased with both candidates. The most recent Real Clear Politics average gives Clinton a 55% unfavorable and Trump a 58.8% unfavorable.

This has contributed to the sense that some have that this election comes down to the lesser of two evils. And indeed, many have strong senses of which one of those evils is lesser. My interest in this post is not to give a comparison between the two, but rather to think about one set of questions that Catholics should think through before deciding which candidate (if any) one decides to vote for. In yesterday’s post, Christine McCarthy discussed the importance of conscience. In today’s post, I’d like to talk about “cooperating with evil.”

There are three ways one can cooperate with evil:

(1) Formal cooperation

Formal cooperation means that someone is doing an evil act and you agree with their intention to do it. This kind of cooperation is never justified, precisely because it means one is intending an evil act.

(2) Immediate Material cooperation

Material cooperation generally means that someone provides some assistance towards achieving the evil end; that assistance is the “material” part or the stuff that makes it possible. In this case, the one assisting does not share the evil intention. The immediate part means that this material cooperation is necessary for the evil outcome to happen. This is typically not justified either, unless the person is under duress.

(3) Mediate Material cooperation

What makes this form of material cooperation mediate is that while one’s aid helps the evil intention to occur, it is not necessary or it does not directly contribute. This is morally justified so long as the good that will result is proportionate to the harm that will be cause and the cooperation doesn’t lead to scandal (scandal meaning it’s likely to cause others to sin too).

What do these forms of cooperation mean for voting? At best, voting is a version of the third form of cooperation. Your vote is not in itself an essential part of the person getting elected (i.e. if you didn’t vote, the person you would have voted for almost certainly would still get elected), particularly when you consider how large the US electorate is. You don’t agree with the candidate’s evil positions, but you earnestly believe (after a responsible examination of conscience) that the good of that candidate outweighs his/her bad. The good achieved by voting for that candidate will outweigh the bad.

However, when someone votes for a particular candidate because of their evil intentions, or when the voter shares those evil intentions, this is formal cooperation with evil. Because the voter is now making a decision precisely because of evil intention, this kind of vote is never morally justified.

What does this mean for the current election? To illustrate, I will offer one (and only one) example from each candidate where their campaign statements are contrary to Catholic teaching.

Clinton has stated that she will work to “defend access to…safe and legal abortion.” Abortion in this sense (sometimes called “direct abortion”) is the intentional termination of a pregnancy, which is considered evil in Catholic teaching. The basic moral argument is that it constitutes an example of the intentional targeting of an innocent life, and thus it can never be justified.

Trump, in reference to what to do about terrorists, has said that “you have to take out their families.” While he later tried to dial down this claim, as described it also sounds like intentional targeting of innocent lives. “Take out” in this context is a fairly clear reference to killing, he didn’t speak in terms of these persons as “collateral damage,” and there’s no suggestion that the families would need to be directly involved in terror to be targeted.

In both these cases, if one votes for Clinton or for Trump and agrees with their respective plan, that would be formal cooperation with evil, and thus never acceptable. If one recognizes that the given policy is morally wrong, and yet in good faith believes that, despite this, the good that would come from a Clinton or a Trump presidency is proportionate to the bad, then that voter is cooperating in a mediate material way.

It’s worth noting that this idea of proportion is essential to justifying mediate material cooperation. The good must outweigh the evil. In the context of deciding whom to vote for, we must take account of both the whole of their policies and compare the candidates on a variety of issues. Usually, this means taking a wide variety of issues into account when choosing for whom to vote. If one chooses to vote on a single issue, one must be able to make a strong case for why a particular candidate’s position on that issue is enough to outweigh the importance of other issues collectively.

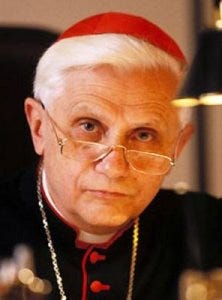

As a final word, some will understandably question whether they can vote at all for a figure who supports evil. During the debate in the US in 2004 about whether a pro-choice politician could receive communion, then-Cardinal Ratzinger sent a memo to Cardinal McCarrick of Washington, DC. At the end, he noted the particular situation of the voter, saying this:

A Catholic would be guilty of formal cooperation in evil, and so unworthy to present himself for Holy Communion, if he were to deliberately vote for a candidate precisely because of the candidate’s permissive stand on abortion and/or euthanasia. When a Catholic does not share a candidate’s stand in favour of abortion and/or euthanasia, but votes for that candidate for other reasons, it is considered remote material cooperation, which can be permitted in the presence of proportionate reasons.

What he argues here is that it is possible to vote for someone who is pro-choice or pro-euthanasia so long as (a) one does not share that sinful intention and (b) there good that comes from that candidate is proportionate to the bad. This logic can, presumably, be applied to other forms of evil that candidates might support.

If you find yourself among the sizable portion of the electorate that sees both these candidates as seriously flawed, it may seem reasonable to decide not to vote for either (or not to vote at all). However, if you can discern that one candidate is better than the other (or simply one is more awful than the other), then there are good, moral grounds to justify voting for one over the other. But this discernment must be done in good faith and in light of one’s conscience.