A High Priest who is Able to Sympathize with our Weaknesses

Part VIIIb of the Celluloid Christ series

“For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin.” (Hebrews 4:15)

“I was very zealous about making a film about Jesus, ultimately to engage the spectator and make it accessible to a modern viewer…And to make Jesus’s character according to the Kazantzakis book, which is fully divine and human—but the fully human side, so human that those in the audience who were despairing and saying, ‘Oh, I’m no good, I’ve done this ,I’ve done that, and I pray to Jesus but that’s not going to help me’—And no, he feels the same way in the film. So he knows, you know. He knows.” - Martin Scorsese1

I wrote yesterday about the depiction of temptation in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, arguing that the anger over what is depicted in the actual last temptation is, in a real way, missing the point.

Instead, the frustrating thing about Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ is Jesus himself. In order to explain, I think it helps to look first at the points in the story where Jesus pivots in his spiritual journey.

As noted yesterday, when we first meet Jesus, he is a carpenter making crosses for the Romans. After he finishes planing an upper crossbar, he faces it and leans against it, stretching his arms across almost as though this one is for him. Judas enters the shop, yells at him for making crosses, and calls him a disgrace. Judas asks him “how will you ever pay for your sins,” and Jesus says “with my life, Judas. I don’t have anything else.” Judas is actually concerned for Jesus, and the end of the confrontation is almost tender. It’s clear here that Jesus and Judas already know each other, although it’s not clear how.

At this point, Jesus is motivated by his fear, by the voices he hears, by his terrible perception of God’s love. When he tells Mary Magdalene that he’s going into the desert, she says he is only doing so because he’s scared.

When he does go to the desert, he meets an old monk. The monk welcomes him, tells him the old master of the monastery has died, and reveals that he knows who Jesus is. The next day, Jesus joins the other monks. As they prepare their old master for burial, Jesus sees it was the same man who met him the night before, even though he had already been dead by that point. One of the younger monks notes that Jesus is blessed that God makes himself known to Jesus.

Later in his hut, Jesus sees a snake slither out of the ground. It speaks in Mary Magdalene’s voice, saying “I forgive you.” The younger monk witnesses this and tells Jesus that he has been purified, but must now go and speak to the people. As Jesus exits to leave, Judas is there, having received orders from his fellow zealots to kill Jesus.

Here we see Jesus pivot from fear to love. Jesus says he pities men, even all living creatures, as he sees the face of God in all of them. He plans to go and speak, and simply let God’s voice come through whenever he opens his mouth. Judas, again somewhat confused by his friend, decides not to kill him, but rather to go with him. Judas in fact is the first disciple, although he ominously warns Jesus “Just so there’s no mistake, I’ll go with you until I understand. But if you stray this much from the path, I’ll kill you.”

After saving Mary Magdalene from stoning and drawing his next batch of disciples, Jesus goes to John the Baptist at the Jordan. After the baptism, the two speak by a fire. John tells him that it’s not just love, that love requires change, even anger. He reminds him of Sodom and Gomorrah. John says that God gave him an ax, for chopping down the rotten tree.

John gives the ax, metaphorically, to Jesus. Jesus heads off to the desert, experiences his temptations (as analyzed yesterday), and eventually returns to his disciples. When he does, he tells them that he has come to baptize with fire and is inviting them to a war. He even says “I believed in love, now I believe in the ax.” At this, Judas bows and calls him “Adonai.”

The pivots from fear to love to the ax, and that each of these three will recur in the film, are the backbone of this portrayal of Jesus. Even as he takes the ax with him to the Temple, overturning tables and driving out moneychangers, there are swings between prophetic certainty and fear that God is not with them.

It is during their time in Jerusalem that Jesus realizes that he will have to die. He tells Judas he had a vision of Isaiah and the suffering servant. Judas calls Jesus out on his inconsistency - he’s gone from love to the ax to death. Judas doesn’t believe what Jesus tells him, but he remains with him nonetheless, possibly still in hope that Jesus will lead the revolution against the Romans.

When they re-enter Jerusalem, this time with the palm fronds and the donkey, Jesus’ followers are expecting revolution. Jesus prays in voiceover “give me a sign, give me the ax, not the cross,” but then his hands bleed like the stigmata. He becomes weak, and Judas helps him walk off. The two talk in an alley, and it is here that Jesus tells Judas that Judas must betray him. Judas is the stronger of the two, and this is why God has given Judas the harder of the two jobs. Moreover, Jesus reminds Judas of his prior promise to kill Jesus if Jesus turns even a little from the path of revolution.

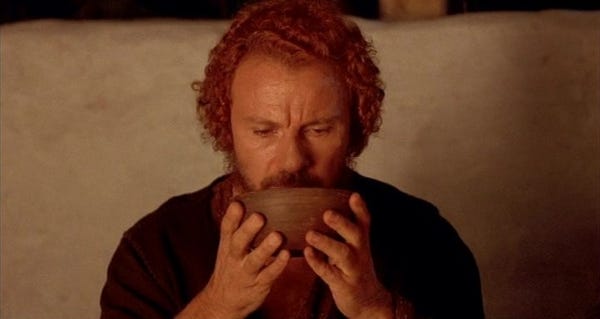

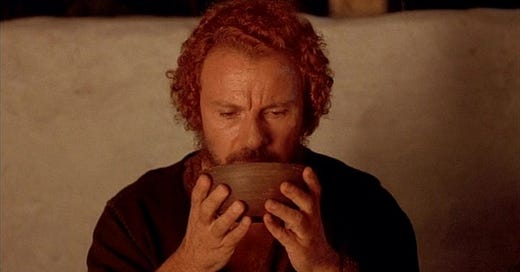

Later, during the Agony in the Garden, Jesus’ internal prayer is an extended version of what one sees in the synoptic Gospels. He compares his call to that of Noah, Moses, and Elijah, who were not called to die. He essentially begs to be released, but then sees an angel in the form of one of his apostles offering him a cup. Jesus accepts, saying “alright, please, just give me the strength to drink.”

Following this, Judas returns with soldiers, kisses Jesus fully on the mouth, and the two men hug. Jesus tells him “take me with you, I’m ready.” It seems that Jesus has finally planted himself on the side of the cross.

Of course, while on the cross, Jesus experiences the last temptation, a vision of a normal life with family, with children. But recall that what snaps Jesus out of this vision, what calls him back to reality and back to the cross, is the condemnation of Judas. He is the one who sees that the guardian angel is Satan.

Who is Jesus in the film? Scorsese set out to show a Jesus who is like us in all things, including sin. Although it’s not evident from the film that we see Jesus actually commit any sins, he is confident throughout that he is a sinner, that he sinned against Mary Magdalene, that he sinned against his mother, that he sinned against God. And he is uncertain, twisting from a paralyzing fear to a merciful love to a prophetic ax, eventually alighting on a self-sacrificial cross that is the conclusion of the merciful love. He is a Jesus who knows himself only slightly, is frightened of who that might be, and who searches, and sometimes dodges, who he is.

In reviewing The Last Temptation of Christ for At the Movies, Gene Siskel evoked precisely what Scorsese was going for:

“The effect, at least on me, was not to trash Jesus, but rather to make his message more accessible. For if he has doubts and fears, we can be more comfortable with our own…if he can resist temptation after really struggling with it, maybe we can too.”

His cohost, Roger Ebert, agreed, noting he also had a religious experience watching the film:

“This movie made me think more deeply and more seriously and for a longer time - I’m still thinking about it - about the mystery of the fact that Jesus is both God and man, at least within the Christian teaching, than any other film I’ve ever seen, or in any other time in my life, did I really confront that, that he was God and he was man. He has all of the weaknesses of man, plus all of the strengths of God. And this movie is a devout movie that does Jesus the compliment of taking him more seriously than any other movie ever made.”

It might seem easy to dismiss Ebert here, but it is striking when he claims this movie prompted so much reflection from him on how to think about Jesus. Later in life, Ebert wrote about his own spiritual development and his quest for understanding, which began for him in his Catholic family and Catholic grade school. He talked of his delight at discussing big questions with his friends and his teachers, recognizing that “religion class began the day with theoretical thinking and applied reasoning, and was excellent training.” He continued to wrestle, it seems for the rest of his life, with the question of whether there is a God and what that God must be like, a question he sought insight about from religion, from science, and, as evidenced by that review, from the movies he watched.

Seeing Ebert’s comments on The Last Temptation of Christ and putting that in the context of his writing on his spiritual life, I at last had an insight on why I responded so strongly to the novel during college. I encountered Kazantzakis while deep into a particular mode of spiritual search, one that was generally, not specifically, Christian, untethered to any particular community or institution. I was spiritually Christian but not really religious.

I think that most people who describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious” (or a variation on that theme) are usually in a transitional stage of discernment. They are either on their way into a religious community and tradition, or on their way out. The Jesus of Last Tempation is also a man in transition, whose discernment of the spirits has come to an impasse, one that must be dealt with. He has been making crosses for some time when we first meet him, but the one that opens the film is the last we see him make. He embarks on a journey that includes seeking forgiveness, self-purification, community, and purpose. He struggles with purpose, even as he realizes what that purpose is. And when at last Jesus cries out “It is accomplished!” the relief is not so much about the salvation of humanity but about finding the answer to the questions that drove him. I wanted an “it is accomplished” moment for myself.

The Jesus directed by Scorsese, the Jesus described by Ebert, is a Jesus for people who want a Jesus that is looking for answers. But this same Jesus is ultimately repellent for people who want a Jesus that is the answer. A Jesus who struggles with his own sinfulness is not a Jesus that can save us from our sins.

One of the ironies that comes from this is an even greater sympathy for Judas. The Last Tempation’s Judas is also on a spiritual journey, one that begins in violence but ends in a loving if painful submission to the will of his messiah. Much as Jesus of Nazareth portrayed Judas not as a villain but as a dupe, The Last Temptation portrays him not as a villain but as a hero, perhaps the truest and greatest of the disciples. And when this Judas calls out the Jesus of the final vision, he’s right. Judas the apostle should be jarring warning about our own propensity to betray Jesus for usually the dumbest of reasons, not an icon of how we must be willing to set aside our own desires to fulfill the call of the lord.

Scorsese’s movie is well acted, beautifully shot, and is often visually evocative, even profound. It’s a great adaptation of the novel, too, a novel that still holds a special place in my heart for its role in my journey. But I think I’m well past the stage of my journey where seeing Jesus in this light is helpful. I feel quite a bit like Paul in the vision of the last temptation: “You know I’m glad I met you, because now I can forget all about you. My Jesus is much more important and much more powerful.”

Stray thoughts about The Last Temptation of Christ:

It does strike me that during the last temptation vision, his mother is not shown. She isn’t there for the wedding, she doesn’t picnic with him and the children. It might have fit well with the guardian angel/Satan’s efforts to keep away characters that might rouse Jesus out of his temptation, which she does with Paul and later with the other apostles.

Something I’ve been tracking and will return to when the series is over: in this film, Judas very clearly drinks from the cup during the last supper. Regarding the bread, we neither see him consume or decline to consume, so eating the bread is probably implied.

Soundtrack by Peter Gabriel is phenomenal and adds so much to the film. For me, the tracks “A Different Drum” and “It is Accomplished” are personal favorites and function really well in their respective scenes. In the series so far, only the Pasolini and Scorsese movies have had soundtracks that have felt so evocative and deliberate.

My pal Andy reminded me of one of David Tracy’s stories: he was invited to a pre-release showing of the film for religious figures. Partway through the film, there was some problem with the projector, so while they stopped to fix it, studio people got food and drinks for everyone. Once it was working again, as they sat there with popcorn while watching Christ be crucified, Dan Berrigan leaned over to Tracy and said “well what are we supposed to do now?”

Next time in the Celluloid Christ series: Jesus of Montreal (1989), directed by Denys Arcand. You can find links to all the posts as they come out in the series page.

Lindlof, Hollywood Under Siege, 13-14.

I did a whole project on Jesus movies in grad school and this post brought back so many memories! Last Temptation of Christ has such a specific (bizarre) feel. And, yes, "A Different Drum" is such a great piece of music. This was my top list at the time (which covers most of the same ground as you) https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/five-jesus-movies-that-dont-stink/ although I think now I would cut out Babette's Feast and replace it with an Au Hasard Balthasar/Eo double feature