1st Sunday of Lent: “one who has similarly been tested in every way”

When I was a junior at Georgetown, I was part of a Bible study on the Gospel of Mark. Although I had been raised as a sort of lackadaisical Presbyterian, I had been trending towards Catholicism for several years (thanks to my Jesuit high school and Jesuit college). I had not yet been baptized, and at the time I was feeling somewhat stagnant in my prayer and faith life. Reading Mark with others, it occurred to me that Jesus’ ministry really began after his baptism, so maybe it was time for me to accept the grace of baptism and get a move on (even in my conversion I was a bit of a narcissist).

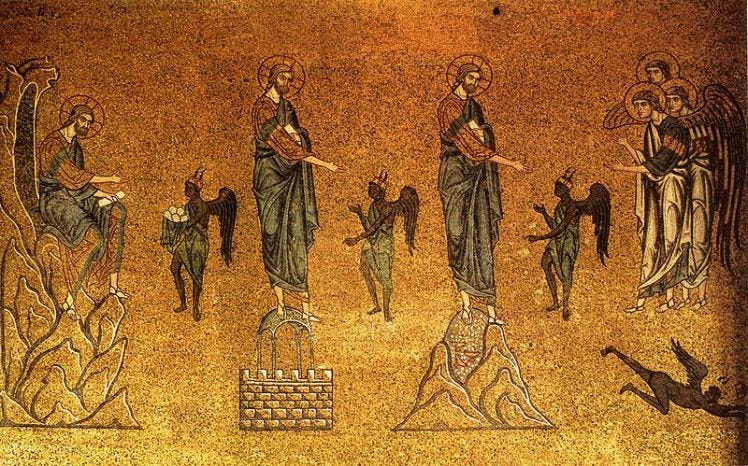

Yet what follows Jesus’ baptism isn’t the beginning of his public ministry, but rather his temptation. And being baptized at the Easter Vigil a few weeks before graduating, I often joked that I too would spend some time in the desert as I headed off to the University of Chicago Divinity School. Surely the heathens there would find all manner of stones for me to turn into bread (critical theory! history of religions!), or would find a high mountain to offer me the kingdom (tenure track!), but I would resist them through the queen of the sciences (theology!).

Again, a touch of the narcissism.

And really, these were not the temptations. What I struggled with then, and what I have struggled with since, is more insidious. Although I can’t claim to say this for all of us who go into academic theology, I know for me it was a choice borne out of my spirituality. I desire to know more about God, about Jesus, about my community, and about my faith. And I think I’m reasonably talented at it – a gift from God, even – so it made sense to me to follow this path. Yet in making an offering of these gifts, I have at different times fallen prey to two particular temptations: (1) impostor syndrome and (2) substituting my intellect for my faith.

First, Impostor syndrome means that I am consistently afraid others will discover that I don’t know what I’m doing. I’m a phony – not a real theologian – and at some point I’ll be found out. Maybe it will be at a conference, or in the classroom, or in an article I submit. The work I do isn’t good enough, isn’t smart enough, and doggone it, people will find out I’m a fraud. Even worse, at times I want to twist this into a virtue – it’s just my way of being humble. But it’s not true humility, because it’s rooted in a misguided, inaccurate understanding of my true self.

Second, I am often tempted to let the academic part of my life dominate my faith. Rather than follow the Benedictine insight of ora et labora and let my academic work be prayerful, I regularly let the labora take the place of any ora. I used to spend the homily at mass critiquing every little thing the preacher said, wondering where they did their academic formation, and thinking of it the way I do conference presentations. Now, more often than not, I tune out during the homily…and rather than making it a time of prayer, I think about my to do list for the day. Most simply, when I’m willing to accept my talent and ability for theology, I am tempted towards thinking that I’m spiritually superior to others.

In truth, both of these are reflections of pride in my life. In the first, a disordered sense of self leads me to put myself down, to see myself as far less valuable than I really am. In the second, the disordered sense of self puffs me up and seeks to place me above others.

These are my temptations (among others), but I think we all have our own. The truth is, I’m not entirely sure we ever get out of the desert. I continue to be tempted.

What gives me hope in temptation though is these stories of Jesus’ temptation in Luke (as well as Matthew and Mark). It reminds me of Hebrews 4:15: “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin.” Although Jesus did not give into temptation and fall into sin (as the rest of us do), it moves me deeply to know that he shared this with us. There are numerous interpretations of what Jesus’ temptations represent, but perhaps most deeply they signify that temptation is part of being human. It gives me a newer insight to when Jesus prays in Matthew “lead us not into temptation.”

As this season of Lent continues and we struggle with our own temptations (and as we fail at prayer, fasting, and almsgiving), let us be hopeful in recalling the temptation and struggle of the One who frees us from sin.